Leopold I of Belgium

Leopold I of Belgium began life as a minor German prince. He served as a Russian general against Napoleon, married into the British and French royal families, and was offered two separate crowns of his own. As the first king of the Belgians, Leopold consolidated Belgium’s independence and ensured that Belgium’s interests were considered by the great powers. He was also the uncle of both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Leopold I, King of the Belgians, by Nicaise de Keyser, 1856

Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld

Leopold was born on December 16, 1790 in Coburg, Germany. At the time, Germany did not exist as a country. It was made up of many small territories, most of which were part of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by Austria. Coburg was in the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. Leopold’s grandfather was the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld and Leopold’s father, Francis, was heir to the duchy. Francis and his wife, Countess Augusta of Reuss-Ebersdorf, had seven children who survived to adulthood. Leopold was their youngest. He was named after Leopold II, the Holy Roman Emperor.

When Leopold was two years old, the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld became caught up in the wars between Revolutionary France and its neighbours. Leopold’s father – a bookish art connoisseur – was commissioned into the Austrian army. A number of French emigrants and noble families from the Rhine and Westphalia fled to Coburg for refuge. This exhausted the resources of the little duchy, which was already heavily indebted.

Despite their impoverished circumstances, the Coburgs were able to secure an important dynastic match. In 1795, a Russian general in search of a bride for Grand Duke Constantine (grandson of Empress Catherine the Great) fell ill and had to stop in Coburg. While there, he was charmed by Leopold’s three oldest sisters. When Empress Catherine invited the girls and their mother to St. Petersburg, Leopold went along. In February 1796, Leopold’s sister Juliana (who took the Russian name of Anna Feodorovna) married Grand Duke Constantine. The marriage did not last. Constantine treated Juliana cruelly and in 1801 she left him for good.

In the meantime, young Leopold became a member of the Russian Imperial Guard. He started as a captain in an infantry regiment, was transferred to a horse regiment as a colonel, and, at the age of 12, became a major general. These were honorary appointments and Leopold did not spend the whole time in Russia, but they were important to his later military career.

In 1800, Leopold’s grandfather died and Leopold’s father became the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. Leopold later wrote:

My poor father, whose health had been shattered early, was a most lovable character…. He was passionately fond of the arts and sciences. My beloved mother…had a warm heart and a fine intellect…. Without wishing to say anything against the other branches of the house of Saxony, ours was certainly the most intellectual. (1)

Leopold inherited his parents’ love of learning. He studied Christianity, Latin, ethics, logic, history, and the law of nations. In addition to his native German, he mastered French, English, Italian and Russian; he could later manage in Spanish and Flemish as well. He cultivated his interests in botany, drawing, and music. He also applied himself to his military studies, something that would prove useful as the wars between France and other European countries continued under Napoleon, who became Emperor of the French in 1804.

Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, by George Dawe, circa 1823-25

Fighting against Napoleon

In 1805, Leopold made his first real appearance in the Russian army. He joined the headquarters of Grand Duke Constantine’s brother, Tsar Alexander I, in Moravia. Thus he was part of the Tsar’s retinue at the Battle of Austerlitz (December 2, 1805), in which Napoleon secured a major victory over Russia and Austria.

In 1806, Napoleon reorganized part of Austria’s territory into the French-controlled Confederation of the Rhine. This marked the demise of the Holy Roman Empire. The French occupied Coburg and then took Saalfeld. On December 9, 1806, Leopold’s father died. On December 15, Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld became part of the Confederation of the Rhine.

In 1807, Leopold again served with Russian forces against France. This time he was with Grand Duke Constantine. He distinguished himself at the battles of Guttstadt-Deppen, Heilsberg and Friedland. The last battle was a decisive French victory. Even though Leopold and other Coburgs had fought against him, Napoleon allowed Leopold’s eldest brother, Ernest, to take possession of the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld under the Treaty of Tilsit (July 7, 1807). In November, Ernest and Leopold went to Paris to thank Napoleon.

Leopold met Napoleon a second time at the Congress of Erfurt in October 1808, as part of Tsar Alexander’s suite. Leopold wanted to continue his military career with Russia, but Napoleon made clear that Ernest would lose his duchy if Leopold did so. Napoleon wanted Leopold to enter France’s service, but Leopold declined.

In 1813, after Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of and retreat from Russia, Leopold rejoined the Russian army, again under Grand Duke Constantine. He commanded a body of Russian cavalry in a series of engagements, including the battles of Lützen and Bautzen. His bravery at the battles of Kulm and Leipzig was rewarded with military decorations. In January 1814, Leopold and his cavalry entered France. They took part in the battles of Brienne, Arcis-sur-Aube, Le Fère Champenoise and Paris. Leopold witnessed the fall of Napoleon and the accession of King Louis XVIII to the French throne.

Marriage to Princess Charlotte of Wales

The Betrothal of Princess Charlotte and Prince Leopold, in the manner of George Clint, circa 1816

In June 1814, Leopold accompanied Tsar Alexander on a celebratory visit to England. While in London, the handsome 23-year-old general met 18-year-old Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales. She was the only legitimate child of King George III’s oldest son, George, Prince of Wales (known as the Prince Regent, later King George IV). Charlotte was engaged to Prince William of Orange, the son of King William I of the Netherlands, but she broke this off.

Leopold went back to the continent to attend the Congress of Vienna. When Napoleon escaped from Elba and returned to France in March of 1815, Leopold rejoined the Russian army. Russia did not participate in the Waterloo Campaign, but Leopold did spend time in Paris after Napoleon’s removal from the French throne. During this period, he and Charlotte corresponded privately. In late 1815, Charlotte informed her father that she favoured Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld as a candidate for her hand.

The Prince Regent invited Leopold to return to England. Doubts about the suitability of a poor, low-ranking German prince for the woman who was second-in-line to the British throne were soon dispelled. Leopold charmed the Prince Regent and those around him. Alicia Campbell, a governess of Princess Charlotte wrote:

I have heard nothing but good of [Prince Leopold]. I inquired of military men in London, who I could depend upon being open and candid with me, and the account was that he is a sensible and rather reserved man, and not dissipated as the generality of foreign princes are. (2)

Charlotte enthused:

No royal marriage I believe, ever promised to the individuals what this one does in point of domestic comfort, as without exaggeration I think I may say that [Prince Leopold] is a very charming and very superior person. (3)

Their engagement was formally announced in the House of Commons on March 14, 1816. Leopold was given British citizenship and the rank of general in the British army. Parliament granted the couple a stipend of £60,000 per year and purchased the estate of Claremont, southwest of London, as a residence for them. This was a huge step up for Leopold. His previous income was probably no more than £400 per annum. (4)

On the evening of May 2, 1816, Leopold and Charlotte were married in the crimson drawing room of Carlton House, the Prince Regent’s London home. Salvoes of artillery from St. James’s Park and the Tower of London announced the event to the city.

When Napoleon, in exile on St. Helena, learned of the match he said:

Prince Leopold was one of the handsomest and finest young men in Paris, at the time he was there. At a masquerade given by the Queen of Naples, Leopold made a conspicuous and elegant figure. The Princess Charlotte must doubtless be very contented and very fond of him. He was near being one of my aide-de-camps, to obtain which he had made interest and even applied; but by some means, very fortunately for himself, it did not succeed, as probably if he had, he would not have been chosen to be a future king of England. (5)

Leopold and Charlotte were happy together. The English painter Thomas Lawrence – commissioned by the Prince Regent to paint a portrait of Charlotte, who was then pregnant – spent time with the couple at Claremont in 1817. He reported:

It is exceedingly gratifying to see that [Princess Charlotte] both loves and respects Prince Leopold, whose conduct, indeed, and character, seem justly to deserve those feelings. From the report of the gentlemen of his household, he is considerate, benevolent, and just, and of very amiable manners. My own observation leads me to think that, in his behaviour to her, he is affectionate and attentive, rational and discreet; and, in the exercise of that judgment which is sometimes brought in opposition to some little thoughtlessness, he is so cheerful and slyly humorous that it is evident…that she is already more in dread of his opinion than of his displeasure.

Their mode of life is very regular: they breakfast together alone about eleven; at half-past twelve she came in to sit to me, accompanied by Prince Leopold, who stayed [a] great part of the time; about three, she would leave the painting-room to take her airing round the grounds in a low phaeton with her ponies, the Prince always walking by her side; at five, she would come in and sit to me till seven; at six, or before it, he would go out with his gun to shoot either hares or rabbits, and return about seven or half-past; soon after which, we went to dinner, the Prince and Princess appearing in the drawing-room just as it was served up. Soon after the dessert appeared, the Prince and Princess retired to the drawing-room, whence we soon heard the pianoforte accompanying their voices…..

After coffee, the card-table was brought, and they sat down to whist, the young couple being always partners, the others changing…. The Prince and Princess retire at eleven o’clock. (6)

Charlotte’s death

On November 3, 1817, Charlotte went into labour. Fifty hours later, on the evening of November 5, she delivered a 9-pound stillborn son. It was a breech birth, poorly managed by Charlotte’s doctor, who committed suicide three months later. Leopold told Thomas Lawrence:

She had been…for many hours, in great pain – she was in that situation where selfishness must act if it exists – when good people will be selfish, because pain makes them so – and my Charlotte was not…. She thought our child was alive; I knew it was not, and I could not support her mistake. I left the room for a short time: in my absence they took courage and informed her. When she recovered from it, she said, ‘Call in Prince Leopold – there is none can comfort him but me!’ …

My Charlotte thought herself very ill, but not in danger. And she was so well but an hour and a half after the delivery! And she said I should not leave her again – and I should sleep in that room…. (7)

On November 6, 1817, five and a half hours after her son’s delivery, Charlotte died of postpartum hemorrhage and shock. She was 21 years old. The governess Mrs. Campbell wrote on November 11, “Prince Leopold is calm, and exerts himself all in his power. He sees us all, and even tries to employ himself; but it is grief to look at him. He seems so heartbroken.” (8)

When Thomas Lawrence brought his finished portrait of Charlotte to Claremont, he met with Leopold.

The Prince was looking exceedingly pale; but he received me with calm firmness, and that low, subdued voice that you know to be the effort at composure. He spoke at once about the picture and of its value to him more than to all the world besides. From the beginning to the close of the interview, he was greatly affected. He checked his first burst of affection, by adverting to the public loss, and that of the royal family. ‘Two generations gone! – gone in a moment! I have felt for myself, but I have felt for the Prince Regent. My Charlotte is gone from this country – it has lost her. She was a good, she was an admirable woman. None could know my Charlotte as I did know her! It was my happiness, my duty to know her character, but it was my delight.’ (9)

Prince Leopold the widower

Prince Leopold, by Thomas Lawrence, 1821

Although he was no longer in line to become prince consort, Prince Leopold remained in England. He received an annuity of £50,000 per year and continued to be addressed as a Royal Highness. He moved into Marlborough House in London. The Crown had bought the residence for the royal couple in 1817, but Charlotte had died before the purchase was completed.

Leopold continued to miss Charlotte. On a visit to Coburg in 1819, he wrote to Alicia Campbell:

[T]he young and happy ménage of my brother [Ernest], as well as the sight of his fine child, gave me almost more pain than I had strength to endure. Time, which softens by degrees the most acute feelings, has kindly exercised its power on me; more accustomed to the sight of these objects I enjoy now somewhat more tranquility, but still I avoid as much as possible the sight of the poor little child. …

Do you think the bustle of this life has already effaced Charlotte’s memory in the minds of the people? I hope not, but new events exercise a strong influence on the human mind, and for that very reason it is my pride that I am a living monument of those happy days that offered to the country such bright prospects; and so I trust it will be made difficult to them to forget Charlotte as long as they see me.

I should already sooner have thought of returning to dear old England, but I greatly wanted quiet and retirement, fallen from a height of happiness and grandeur seldom equalled, to accustom myself to the painful task of leading so very different a life. … My health is rather improved, but still not what it was in 1817, and probably never will become so again. (9)

Three months later, Mrs. Campbell visited Leopold in London.

The Prince has laid out a great deal of money on Marlborough House, in painting and cleaning it, very handsome carpets to the whole range of apartments, and silk furniture, and on my asking if the silk on one sofa was foreign, he seemed quite to reproach me, and said I should never see anything that was not English in his house that he could avoid. I could not help wishing that Mrs. Williams had been with us to judge of the sum that Prince Leopold must have expended in the last three months on English manufactures – magnificent glass lustres in all the rooms, &c. He has also purchased a large collection of fine paintings, which are coming over, and though that is giving money out of the country, it brings a value back.

The Prince told me that it was a painful task to attend the christening at Kensington, but he thought it right. (10)

The christening in question was that of Leopold’s niece, the daughter of his sister Victoria and the Duke of Kent. The baby, Alexandrina Victoria, was born on May 24, 1819 and baptized on June 24. In 1837, she became Queen Victoria. She remained close to her uncle Leopold throughout his life.

Leopold was a congenial host and invitations to his parties were highly sought. It is at one of Prince Leopold’s soirees that Lord Liverpool and the Duke of Wellington learn of Napoleon’s (fictional) escape from St. Helena in my novel Napoleon in America.

In 1828-29, Leopold had a relationship with a German actress named Caroline Bauer, a cousin of his physician and advisor, Christian Friedrich von Stockmar. Caroline claimed in her memoirs, published after her death, that she and Leopold entered into a morganatic marriage, although there is no evidence of this.

On the Belgian throne

In 1830, the great powers recognized Greece as an independent state. They offered Prince Leopold the opportunity to head the new monarchy – in fact, they proclaimed him sovereign of Greece – but Leopold declined on the grounds that he had not been accepted freely and unanimously by the Greek nation. Later that year, when Belgium declared its independence from the Netherlands, the great powers again sought a neutral candidate for a new throne. After considering, among others, Auguste of Leuchtenberg, who was the son of Napoleon’s stepson Eugène de Beauharnais, they offered the Belgian crown to Prince Leopold. This time he accepted. He renounced his British pension and moved to Belgium. On July 21, 1831, at the Place Royale in Brussels, Leopold was sworn in as King of the Belgians. July 21st is still celebrated as Belgium’s national holiday.

King Leopold had to contend with the tricky challenge of pursuing Belgian national aims while maintaining the support of the great powers. He ably identified himself with his new country and, using his personal connections with other courts, did his best to manoeuvre among the European powers to achieve Belgian goals.

Less than two weeks after Leopold’s accession to the Belgian throne, Dutch troops invaded Belgium. Leopold personally commanded troops to defend his country. When the British government did nothing, Leopold appealed to France for support. The arrival of French soldiers compelled the Dutch to retreat. Periodic skirmishes continued between the Dutch and the Belgians until the Netherlands formally recognized Belgium’s independence in 1839. Belgium also had to pay a large debt to the Netherlands.

Belgium had been established as a constitutional monarchy. Leopold respected the constitution, while guarding his royal prerogatives. He appointed each minister in his cabinet and insisted on being consulted before ministers acted, but did not encroach on their powers. As Belgian independence had been the result of a union between Catholics and Liberals, Leopold tried not to upset this alliance. Until 1847, he was able to choose a broad-based cabinet, consisting of Catholic and Liberal ministers. Afterwards, in recognition of growing political divisions, he had to appoint either all Liberals or all Catholics, depending on who controlled the chamber of representatives. Leopold’s political astuteness meant that Belgium remained relatively untouched by the revolutions that swept Europe in 1848, although his father-in-law, Louis-Philippe of France (see below), lost his throne.

Leopold supported electoral reform and economic modernization. He promoted the establishment of continental Europe’s first passenger rail line, between Brussels and Mechelen, inaugurated in 1835. In 1842, he ordered a special commission to investigate child labour in factories and propose legislation to protect children, but the proposed law was ultimately defeated. He helped the country weather an economic crisis and signed commercial treaties with Prussia, France and the Netherlands.

One of Leopold’s pet projects was an attempt to establish a Belgian colony in the Americas. In 1841, he encouraged a small group of investors to form the Belgian Colonization Company, hoping to take advantage of economic opportunities in Guatemala. In 1843 the company sent some 200 poorly-supplied Belgian settlers and workers to Santo Tomás de Castilla. The settlement grew to include 800 civilians and 48 soldiers. Leopold ordered the Belgian minister to Mexico to negotiate the transfer of sovereignty over Santo Tomás to Belgium, but the Guatemalan government refused. In 1846, a new Belgian cabinet withdrew support for Leopold’s overseas adventure. Many of the settlers died of yellow fever and malaria, and the company ultimately had to withdraw because of financial losses. Leopold bemoaned the failure of the venture. In 1851, he wrote to the Minister of the Interior:

Central America has become very important; it has a future before it, and it is inconceivable how so little interest should be bestowed upon it in Belgium. (12)

When Napoleon’s nephew Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III) staged a coup d’état in France in December 1851, Belgium was thought to be one of the areas he coveted. Leopold described his fears in a letter to his niece, Queen Victoria:

We are here in the awkward position of persons in hot climates, who find themselves in company, for instance in their beds, with a snake. They must not move because that irritates the creature, but they can hardly remain as they are without a fair chance of being bitten. (13)

In the end, an Anglo-French rapprochement protected Belgium. Leopold was able to ensure Belgian neutrality throughout his reign, even during the Crimean War (1853-1856).

On July 21, 1856, Leopold celebrated 25 years on the throne. Étienne Constantin de Gerlache, the first prime minister of Belgium, remarked:

[D]uring these twenty-five years of sovereignty, its king has never violated a single one of its laws, lifted a finger against a single one of its liberties, or given legitimate cause of complaint to a single one of its fellow-citizens. … Amidst the commotions which have shaken so many governments, Belgium has remained faithful to her prince and the institutions she created for herself. This sort of phenomenon, rare as it is in our age, can be explained only by the happy harmony existing between king and people, cemented by their common respect for sworn faith and for the national constitution. (14)

Earlier, in 1854, Leopold had written:

My part is, as it has been since 1831, very simple. I put the ship through the manoeuvre which is necessary to preserve it; about twenty-three years of navigation give some title to confidence. (15)

Marriage to Princess Louise of Orléans

The Wedding of Leopold I of Belgium and Louise of Orléans in the chapel of the Château de Compiègne (1832), by Joseph-Désiré Court, 1837

Leopold had initially been regarded as a British candidate for the Belgian throne. To be viewed as a neutral candidate, he had to marry Princess Louise of Orléans, eldest daughter of King Louis Philippe of France and sister of the Prince of Joinville. Leopold had known Louise since she was a little girl. Her parents had been guests at his wedding to Charlotte.

Leopold married Louise on August 9, 1832 at the Château de Compiègne. She was 20; he was 42. Since Leopold was Protestant and Louise was Catholic, they had a Catholic ceremony in the chapel, after which they repaired to another room for a Lutheran ceremony. On August 17, Leopold wrote, “I am delighted with my good little queen; she is the sweetest creature you ever saw, and she has plenty of wits. This marriage cuts away the pretexts for partition [of Belgium]….” (16)

They had four children, three of whom lived to adulthood: Leopold, Duke of Brabant (April 9, 1835 -December 17, 1909), who became King Leopold II of the Belgians; Philippe, Count of Flanders (March 27, 1837 – November 17, 1905); and Charlotte (June 7, 1840 – January 19, 1927), who became Empress of Mexico. Leopold and Louise raised their children as Catholics because the majority of Belgians were Catholic.

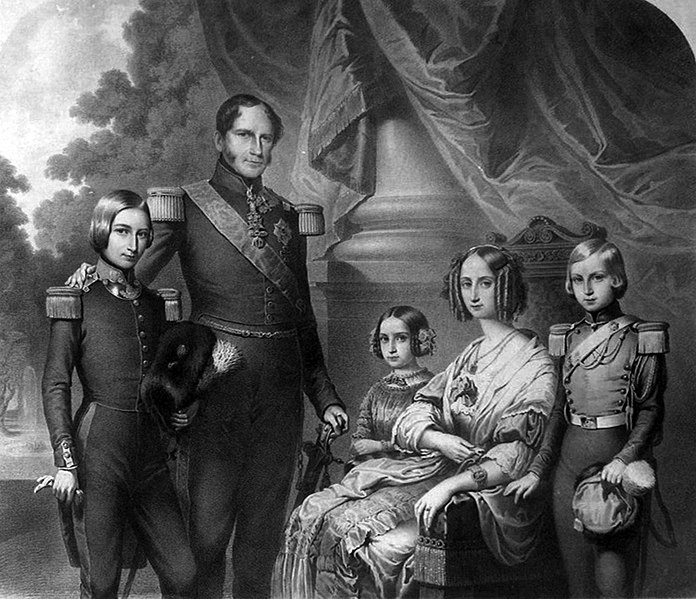

Leopold I of Belgium with his family, by Charles Baugniet, circa 1850. From left to right: Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant (future Leopold II); King Leopold I; Princess Charlotte (future Empress of Mexico); Queen Louise; Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders

Leopold also had two sons with a Belgian mistress named Arcadie Claret. The first, George, was born on November 14, 1849, when Arcadie was 23 and Leopold was 58. The second son, Arthur, was born on September 25, 1852. Before the births, Leopold had Arcadie married to his stablemaster, Ferdinand Meyer, a widower with three children, to reduce the scandal occasioned by their affair.

Queen Louise died of tuberculosis on October 11, 1850, at the age of 38. Arcadie and Ferdinand Meyer separated in 1861. Leopold remained in a relationship with Arcadie until he died.

Connections to the royal families of Europe

Left to right: Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders; Prince Albert, Prince Consort; Princess Alice; Infante Luís, Duke of Porto (future King Luís I of Portugal); Queen Victoria (seated); Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (future King Edward VII); King Leopold I of Belgium. Attributed to Dudley FizGerald-de-Ros, 1859

Because of Belgium’s neutrality and his own personal connections, King Leopold was able to play an influential role in European diplomacy. He skillfully promoted marriages of his family with the other royal families of Europe to strengthen his diplomatic ties.

In 1836, Leopold I of Belgium encouraged the marriage of his nephew, Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, to Maria II, Queen of Portugal. In 1840, he helped to arrange the marriage of his niece Victoria, Queen of England, to his nephew, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Also in 1840, another of Leopold’s nieces, also named Victoria (the daughter of his brother Ferdinand), married the Duke of Nemours, son of King Louis-Philippe of France. Leopold negotiated the marriage of his son Leopold to Archduchess Marie Henriette, daughter of Archduke Joseph of Austria, Palatine of Hungary, in 1853. And in 1857 Leopold’s daughter Charlotte married Archduke Maximilian of Austria, who became the ill-fated Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico.

Death of Leopold I of Belgium

Leopold was in ill health in 1862 and had to submit to several painful operations. A former Belgian cabinet minister who met with Leopold in January 1864 wrote.

Though much tried by lingering pain, he had the uprightness, the old firmness and nobility of attitude, the old kingly bearing; I was, as I had always been, struck with that cold but courteous kindness which marked his official relations: he first discussed seriously the matters which occupied at this time the minds of all; he enunciated his own views, estimated the value of opinions, passed judgment on men and measures, argued out and laid down conclusions; he had still as the vigour of his character, and all the freshness of his mind: then quitting the grave and serious, as apparently done with, he turned the conversation and gave himself up by little and little to that quiet gaiety which was part of his nature, and the expression of which, with its mixture of plentiful anecdote and keen irony, had an irresistible charm. (17)

King Leopold I of Belgium died on December 10, 1865 at the Palace of Laeken, age 74. He was buried in the royal crypt in the Church of Notre Dame de Laeken, in Brussels, with his wife Queen Louise.

Queen Victoria had a monument erected to Leopold’s memory in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, beside the cenotaph of Princess Charlotte. The inscription includes: “This monument was raised by Queen Victoria to the memory of the uncle who held the place of a father in her affections.” (18)

You might also enjoy:

When Princess Caroline Met Empress Marie Louise

Photos of 19th-Century French Royalty

François d’Orléans, Prince of Joinville: Artist & Sailor

Morganatic Marriage: Left-Handed Royal Love

- Théodore Juste, Memoirs of Leopold I, King of the Belgians, translated by Robert Black, Vol. I (London, 1868), pp. 43-44.

- Harriot Georgiana Mundy, ed., The Journal of Mary Frampton (London, 1885), pp. 262-263.

- Ibid., p. 272.

- Arthur Henry Beavan, Marlborough House and Its Occupants: Present and Past (London, 1896), p. 260.

- Barry E. O’Meara, Napoleon in Exile; or, A Voice from St. Helena, Vol. II (London, 1822), p. 33.

- E. Williams, The Life and Correspondence of Sir Thomas Lawrence, Vol. II (London, 1831), pp. 75-76.

- Ibid., pp. 83-84.

- The Journal of Mary Frampton, p. 300.

- The Life and Correspondence of Sir Thomas Lawrence, Vol. II, p. 82.

- The Journal of Mary Frampton, pp. 311-314.

- Ibid., pp. 315-316.

- Arthur Christopher Benson and Viscount Escher, eds., The Letters of Queen Victoria, Vol. II, 1844-1858 (London, 1907) pp. 457.

- Théodore Juste, Memoirs of Leopold I, King of the Belgians, translated by Robert Black, Vol. II (London, 1868), p. 184.

- Ibid., p. 280

- Ibid., p. 292.

- Ibid., p. 75.

- Ibid., pp. 337-338.

- Ibid., p. 384.

17 commments on “Leopold I of Belgium”

Join the discussion

He is a sensible and rather reserved man, and not dissipated as the generality of foreign princes are.

Alicia Campbell

ANOTHER SUPERB ARTICLE. UNFORTUNATE THAT HE WAS PLAYED AS SOMEWHAT MANIPULATIVE AND ALL TOO CUNNING IN THE PBS SERIES ON YOUNG VICTORIA A FEW YEARS BACK.

Thanks, Arthur. I didn’t see that series. Perhaps I should look it up.

Leopold II was truly a monster. His father seems to have been an upstanding, indeed perhaps a truly “noble” man, as the old system of nobility sometimes produced. What went wrong?

Excellent question, Addison. I was wondering that myself.

One happy ending story from the Napoleonic wars. Except for the medical tragedies.

Indeed!

Another wonderful article! heartbreaking about Charlotte. So glad you are still at it, Shannon!

Thanks, Geoffrey!

“In 1828-29, Leopold had a relationship with a German actress named Caroline Bauer, a cousin of his physician and advisor, Christian Friedrich von Stockmar. Caroline claimed in her memoirs, published after her death, that she and Leopold entered into a morganatic marriage, although there is no evidence of this.”

I wonder if Conan Doyle knew about this? It sounds like a possible inspiration for his Sherlock Holmes story “A Scandal In Bohemia”.

I don’t know that story, John. Having now looked up the plot, I can see how Leopold and Caroline might have been an inspiration.

And by Leopold I and Louise d’Orléans, the current Prince Napoléon is a descendant of the first French Bourbon king, Henri IV, of Louis XIV, of Louis-Philippe, quite ironic…

The information about Arcadie Meyer is incorrect – Leopold actually dismissed her as he learned what she and her mother were all about. Arcadie was blatantly unfaithful, so the so-called children are only alleged.

Thanks for your comments. I amended the post to remove the reference to Arcadie being a noblewoman when Leopold met her. I gather that, at Leopold’s urging, Arcadie was given the title of Baroness von Eppinghoven by Leopold’s nephew, the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, in 1863, and the two children were also created Barons.

Arcadie Meyer was NOT a Belgian noblewoman – she was put forward by a social-climbing mother. Some Belgian sources are incorrect as they do not source their claims. Again, Leopold dismissed her due to his own findings about her and pressure from his Cabinet. She and her family were social-climbers and her children turned out as badly as she did.

Thanks for this excellent point, Marie-Noëlle. I hadn’t realized that!

Are you not going to post stories anymore? Your website is one of my favorites.

I’m so glad you’re enjoying the website, Hamilton. That’s very kind of you to say. I’m sorry I haven’t posted for several months. I do intend to write more articles for the site and am working on one that I will be putting up later this month.