When Basil Hall Met Napoleon

Basil Hall was a British naval officer, traveller and author who wrote engaging books about his trips to Asia, South America and North America in the early 1800s. In 1817, Hall met with defeated French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte on the remote South Atlantic island of St. Helena. A dozen years later, Hall’s publication about his travels in the United States caused a “moral earthquake” among Americans. (1)

About Basil Hall

Captain Basil Hall, by Henry Raeburn

Basil Hall was born in Edinburgh on December 31, 1788. His father – Sir James Hall, the fourth Baronet of Dunglass – was a prominent Scottish geologist and geophysicist who later became a member of the British House of Commons. James Hall had visited Brienne, France, when Napoleon was a student at the military academy there, something that later came in handy for his son. Basil’s mother, Helen Douglas, was the daughter of the fourth Earl of Selkirk.

Basil Hall joined the Royal Navy at the age of 13. In 1808, he was commissioned as a lieutenant on the frigate HMS Endymion. As such, he helped British forces evacuate northern Spain at the Battle of Corunna in 1809. In 1812, Hall was sent to the East Indies Station, where he visited India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Borneo and Java. In 1816, he commanded HMS Lyra, a sloop-brig that served as escort on Lord Amherst’s diplomatic mission to China. Hall and his men undertook surveys of the west coast of Korea and the Loo-Choo (Ryukyu) Islands. On the return voyage to England in 1817, the Lyra called at St. Helena, where Napoleon had been imprisoned by the British since 1815.

Basil Hall’s visit with Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte at Saint Helena © The Trustees of the British Museum

At first Basil Hall tried to set up a meeting with Napoleon through St. Helena’s governor, Sir Hudson Lowe. As Napoleon was not on good terms with Lowe, that attempt came to nothing. Hall was then advised to go to Napoleon’s residence, Longwood House, in the hope that Napoleon might decide to see him on the spot. Once there, however, Hall was informed that Napoleon was not in the mood to see anybody. An approach through Napoleon’s “Grand Marshal of the Palace,” General Bertrand, also failed. Hall was finally able to secure an audience with the deposed French emperor by mentioning to Napoleon’s Irish physician, Barry O’Meara, that his father had been at Brienne while Napoleon was there. When O’Meara took this information to Napoleon, the latter agreed to see Hall.

The meeting took place in the afternoon of August 13, 1817, and lasted about 25 minutes. It was conducted in French, as Napoleon did not speak English. Later that day, Hall – who kept a daily journal – wrote down everything he could remember about the conversation. What follows is the account published in his book about his voyage to East Asia.

On Basil Hall’s father

“On entering the room, I saw Buonaparte standing before the fire, with his head leaning on his hand, and his elbow resting on the chimney-piece. He looked up, and came forward two paces, returning my salutation with a careless sort of bow, or nod. His first question was, ‘What is your name?’ and, upon my answering, he said, ‘Ah, – Hall – I knew your father when I was at the Military College of Brienne – I remember him perfectly – he was fond of mathematics – he did not associate much with the younger part of the scholars, but rather with the priests and professors, in another part of the town from that in which we lived.’ He then paused for an instant, and as he seemed to expect me to speak, I remarked that I had often heard my father mention the circumstance of his having been at Brienne during the period referred to; but had never supposed it possible that a private individual could be remembered at such a distance of time, the interval of which had been filled with so many important events. ‘Oh no,’ exclaimed he, ‘it is not in the least surprising; your father was the first Englishman I ever saw, and I have recollected him all my life on that account.’ (2) …

“Buonaparte asked, with a playful expression of countenance…. ‘Have you ever heard your father speak of me?’ I replied instantly, ‘Very often.’ Upon which he said, in a quick, sharp tone, ‘What does he say of me?’ … I said that I had often heard him express great admiration of the encouragement he had always given to science while he was Emperor of the French. He laughed and nodded repeatedly, as if gratified by what was said.

“His next question was, ‘Did you ever hear your father express any desire to see me?’ I replied that I had heard him often say there was no man alive so well worth seeing, and that he had strictly enjoined me to wait upon him if ever I should have an opportunity.’ ‘Very well,’ retorted Buonaparte, ‘if he really considers me such a curiosity, and is so desirous to see me, why does he not come to St. Helena for that purpose?’

“I was at first at a loss to know whether this question was put seriously or ironically; but as I saw him waiting for an answer, I said my father had too many occupations and duties to fix him at home. ‘Has he any public duties? Does he fill a public station?’ I told him, none of an official nature; but that he was President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the duties of which claimed a good deal of his time and attention. This observation gave rise to a series of inquiries respecting the constitution of the Society in question. He made me describe the duties of all the office-bearers, from the president to the secretary, and the manner in which scientific papers were brought before the society’s notice. He seemed much struck, I thought, and rather amused, with the custom of discussing subjects publicly at the meetings in Edinburgh. When I told him the number of members was several hundreds, he shook his head and said, ‘All these cannot surely be men of science!’

“When he had satisfied himself on this topic, he reverted to the subject of my father, and after seeming to make a calculation, observed, ‘Your father must, I think, be my senior by nine or ten years – at least nine – but I think ten. Tell me, is it not so?’ I answered that he was very nearly correct. Upon which he laughed and turned almost completely round on his heel, nodding his head several times. I did not presume to ask him where the joke lay, but imagined he was pleased with the correctness of his computation. He followed up his inquiries by begging to know what number of children my father had; and did not quit this branch of the subject till he had obtained a correct list of the ages and occupation of the whole family.

On Hall’s voyage to Asia

“He then asked, ‘How long were you in France?’ and on my saying I had not yet visited that country, he desired to know where I had learned French. I said, from Frenchmen on board various ships of war. ‘Were you the prisoner amongst the French,’ he asked, ‘or were they your prisoners?’ I told him my teachers were French officers captured by the ships I had served in. He then desired me to describe the details of the chase and capture of the ships we had made prize of; but soon seeing that this subject afforded no point of any interest, he cut it short by asking me about the Lyra’s voyage to the Eastern Seas, from which I was now returning. This topic proved a new and fertile source of interest, and he engaged in it, accordingly, with the most astonishing degree of eagerness. …

“Having settled where [Loo-Choo] lay, he cross-questioned me about the inhabitants with a closeness – I may call it a severity of investigation – which far exceeds everything I have met with in any other instance. His questions were not by any means put at random, but each one had some definite reference to that which preceded it or was about to follow. I felt in a short time so completely exposed to his view, that it would have been impossible to have concealed or qualified the smallest particular. Such, indeed, was the rapidity of his apprehension of the subjects which interested him, and the astonishing ease with which he arranged and generalized the few points of information I gave him, that he sometimes outstripped my narrative, saw the conclusion I was coming to before I spoke it, and fairly robbed me of my story.

“Several circumstances, however, respecting the Loo-Choo people, surprised even him a good deal; and I had the satisfaction of seeing him more than once completely perplexed, and unable to account for the phenomena which I related. Nothing struck him so much as their having no arms. ‘Point d’armes!’ he exclaimed, ‘c’est à dire point de cannons – ils ont des fusils?’ Not even muskets, I replied. ‘Eh bien donc – des lances, ou, au moins, des arcs et des flêches?’ I told him they had neither one nor other. ‘Ni poignards?’ cried he, with increasing vehemence. No, none. ‘Mais!’ said Buonaparte, clenching his fist, and raising his voice to a loud pitch, ‘Mais! sans armes, comment se bat-on?’ [But without weapons, how do they fight?]

“I could only reply, that as far as we had been able to discover, they had never had any wars, but remained in a state of internal and external peace. ‘No wars!’ cried he, with a scornful and incredulous expression, as if the existence of any people under the sun without wars was a monstrous anomaly.

“In like manner, but without being so much moved, he seemed to discredit the account I gave him of their having no money, and of their setting no value upon our silver or gold coins. After hearing these facts stated, be mused for some time, muttering to himself, in a low tone, ‘Not know the use of money – are careless about gold and silver.’ Then looking up, he asked, sharply, ‘How then did you contrive to pay these strangest of all people for the bullocks and other good things which they seem to have sent on board in such quantities?’ When I informed him that we could not prevail upon the people of Loo-Choo to receive payment of any kind, he expressed great surprise at their liberality, and made me repeat to him twice the list of things with which we were supplied by these hospitable islanders.

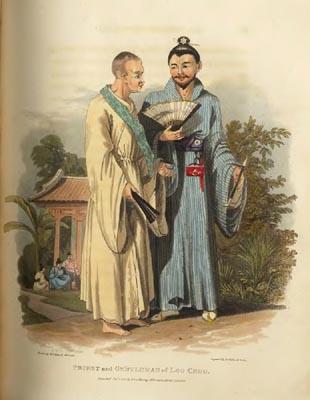

Korean Chief and his Secretary, from Basil Hall’s voyage

“I had carried with me, at Count Bertrand’s suggestion, some drawings of the scenery and costume of Loo-Choo and [K]orea, which I found of use in describing the inhabitants. When we were speaking of [K]orea, he took one of the drawings from me, and running his eye over the different parts, repeated to himself, ‘An old man with a very large hat, and long white beard, ha! – a long pipe in his hand – a Chinese mat – a Chinese dress – a man near him writing – all very good and distinctly drawn.’ He then required me to tell him where the different parts of these dresses were manufactured, and what were the different prices – questions I could not answer. He wished to be informed as to the state of agriculture in Loo-Choo – whether they ploughed with horses or bullocks – how they managed their crops, and whether or not their fields were irrigated like those in China, where, as he understood, the system of artificial watering was carried to a great extent. The climate, the aspect of the country, the structure of the houses and boats, the fashion of their dresses, even to the minutest particular in the formation of their straw sandals and tobacco pouches, occupied his attention. He appeared considerably amused at the pertinacity with which they kept their women out of our sight, but repeatedly expressed himself much pleased with Captain Maxwell’s moderation and good sense in forbearing to urge any point upon the natives which was disagreeable to them, or contrary to the laws of their country.

“He asked many questions respecting the religion of China and Loo-Choo, and appeared well aware of the striking resemblance between the appearance of the Catholic Priests and the Chinese Bonzes; a resemblance which, as he remarked, extends to many parts of the religious ceremonies of both. Here, however, as he also observed, the comparison stops; since the Bonzes of China exert no influence whatsoever over the minds of the people, and never interfere in their temporal or eternal concerns. In Loo-Choo, where everything else is so praiseworthy, the low state of the priesthood is as remarkable as in the neighbouring continent, an anomaly which Buonaparte dwelt upon for some time without coming to any satisfactory explanation.

Priest and Gentleman of Loo-Choo, from Basil Hall’s voyage

“With the exception of a momentary fit of scorn and incredulity when told that the Loo-Chooans had no wars or weapons of destruction, he was in high good humour while examining me on those topics. The cheerfulness, I may almost call it familiarity, with which he conversed, not only put me quite at ease in his presence, but made me repeatedly forget that respectful attention with which it was my duty, as well as my wish on every account, to treat the fallen monarch. The interest he took in topics which were then uppermost in my thoughts, was a natural source of fresh animation in my own case; and I was thrown off my guard, more than once, and unconsciously addressed him with an unwarrantable degree of freedom. When, however, I perceived my error, and of course checked myself, he good-humouredly encouraged me to go on in the same strain, in a manner so sincere and altogether so kindly, that I was in the next instant as much at my ease as before.

“‘What do these Loo-Choo friends of yours know of other countries?’ he asked. I told him they were acquainted only with China and Japan. ‘Yes, yes,’ continued he; ‘but of Europe? What do they know of us?’ I replied, ‘They know nothing of Europe at all; they know nothing about France or England; neither,’ I added, ‘have they ever heard of your Majesty.’ Buonaparte laughed heartily at this extraordinary particular in the history of Loo-Choo, a circumstance, he may well have thought, which distinguished it from every other corner of the known world. …

Back to Hall and his father

“When he had satisfied himself about our voyage, or at least had extracted everything I could tell him about it, he returned to the subject which had first occupied him, and said in an abrupt way, ‘Is your father an Edinburgh Reviewer?’ I answered, that the names of the authors of that work were kept secret, but that some of my father’s works had been criticised in the journal alluded to. Upon which he turned half round on his heel towards Bertrand, and nodding several times, said, with a significant smile, ‘Ha! ha!’ as if to imply his perfect knowledge of the distinction between author and critic.

“Buonaparte then said, ‘Are you married?’ and upon my replying in the negative, continued, ‘Why not? What is the reason you don’t marry?’ I was somewhat at a loss for a good answer, and remained silent. He repeated his question, however, in such a way that I was forced to say something, and told him I had been too busy all my life; besides which, I was not in circumstances to marry. He did not seem to understand me, and again wished to know why I was a bachelor. I told him I was too poor a man to marry. ‘Aha!’ he cried, ‘I now see – want of money – no money – yes, yes!’ and laughed heartily; in which I joined, of course, though to say the truth, I did not altogether see the humorous point of the joke.

“The last question he put related to the size and force of the vessel I commanded, and then he said, in a tone of authority, as if he had some influence in the matter, ‘You will reach England in thirty-five days’ – a prophecy, by the by, which failed miserably in the accomplishment, as we took sixty-two days, and were nearly starved into the bargain. After this remark he paused for about a quarter of a minute, and then making me a slight inclination of his head, wished me a good voyage, and stepping back a couple of paces, allowed me to retire. …

Hall’s impression of Napoleon

“Buonaparte struck me as differing considerably from the pictures and busts I had seen of him. His face and figure looked much broader and more square, larger, indeed, in every way, than any representation I had met with. His corpulency, at this time universally reported to be excessive, was by no means remarkable. His flesh looked, on the contrary, firm and muscular. There was not the least trace of colour in his cheeks; in fact, his skin was more like marble than ordinary flesh. Not the smallest trace of a wrinkle was discernible on his brow, nor an approach to a furrow on any part of his countenance. His health and spirits, judging from appearances, were excellent; though at this period it was generally believed in England that he was fast sinking under a complication of diseases, and that his spirits were entirely gone. His manner of speaking was rather slow than otherwise, and perfectly distinct: he waited with great patience and kindness for my answers to his questions, and a reference to Count Bertrand was necessary only once during the whole conversation. The brilliant and sometimes dazzling expression of his eye could not be overlooked. It was not, however, a permanent lustre, for it was only remarkable when he was excited by some point of particular interest. It is impossible to imagine an expression of more entire mildness, I may almost call it of benignity and kindliness, than that which played over his features during the whole interview. If, therefore, he were at this time out of health and in low spirits, his power of self command must have been even more extraordinary than is generally supposed; for his whole deportment, his conversation, and the expression of his countenance, indicated a frame in perfect health, and a mind at ease.” (3)

American criticism

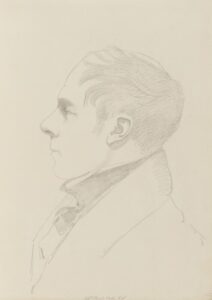

Basil Hall by Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey, pencil, circa 1825-1830, NPG 316a(62) © National Portrait Gallery, London

Once back in England, Basil Hall was promoted to the rank of captain. In 1820, Hall was put in command of HMS Conway, a 26-gun frigate on the South American Station. From 1820-1822 he travelled along the coasts of Chile, Peru and Mexico on a mission to protect British interests in the newly independent Spanish colonies.

Hall retired from the navy in 1823. In 1825, he married Margaret Congalton Hunter (1799-1876), daughter of a former British consul in Spain. Hall and Margaret had one child, Elizabeth (Eliza) Jane.

In 1827, Hall sailed with his wife and daughter to North America, where they travelled around the United States and also visited Canada. Although written in his usual “good-natured, breezy, conscientious, observant manner,” Hall’s frank impressions, laid out in his book Travels in North America in the years 1827 and 1828, caused such an uproar in the United States that some booksellers refused to carry it. (You can read excerpts in my posts about Washington D.C. in the 1820s, John Quincy Adams and the White House Billiard Table, Visiting Niagara Falls in the Early 19th Century, and How did people shop in the early 1800s?.)

Hall was hurt by the American reception of his book and found it hard to understand the criticism.

In all my travels, both among heathens and among Christians, I have never encountered any people by whom I found it nearly so difficult to make myself understood as by the Americans. (4)

Basil Hall’s later life

Basil Hall in later years

In 1831, Basil Hall published the first of his 9-volume Fragments of Voyages and Travels, a description of naval life and adventure “written chiefly for young persons.” This was followed, in 1836, by Schloss Hainfield, or A Winter in Lower Styria, based on time he spent with Jane Cranstoun, the Countess of Purgstall. In 1841 he published Patchwork, a three-volume collection of tales from his travels in Europe.

Sadly, in 1842, Captain Basil Hall was confined as a mental patient at the Royal Naval Hospital Haslar in Portsmouth. He died there on September 11, 1844, at the age of 55.

The Hall-De Lancey Connection

Magdalene (Hall) De Lancey

In April 1815, Basil Hall’s sister Magdalene married American-born Colonel William Howe De Lancy, a friend of Basil’s who had served in the British Army under the Duke of Wellington in Spain. When Napoleon escaped from Elba in 1815, Wellington insisted on having De Lancey appointed as quartermaster general of the army in Belgium, instead of Hudson Lowe, whom Wellington disliked. (Lowe went on to marry De Lancey’s sister, Susan Johnson, and to become governor of St. Helena.)

Since Magdalene and De Lancey were still on their honeymoon, she joined her husband in Belgium. On June 18, 1815, while speaking with Wellington during the Battle of Waterloo, De Lancey was hit in the back by a ricocheting cannonball, which knocked him from his horse. Initial reports said he had died, but he was found alive in a peasant’s cottage, where Magdalene tenderly nursed him. Eight days later, he died of his injuries. At her brother’s request, Magdalene wrote an account of those final days. This was later published as A Week at Waterloo in 1815. Basil Hall shared the narrative with Sir Walter Scott and Charles Dickens, among others. They were very touched by it.

Basil Hall was a gifted writer with keen powers of observation. His books are available for free on the Internet Archive.

You might also enjoy:

When the Duke of Wellington Met Napoleon’s Wife

When Princess Caroline Met Empress Marie Louise

When Louisa Adams Met Joseph Bonaparte

When John Quincy Adams Met Madame de Staël

When an Englishman Met a Napoleonic Captain in Restoration France

- “Captain Basil Hall’s ‘Travels in North America’ [produced] a sort of moral earthquake and the vibration it occasioned through the nerves of the republic, from one corner of the Union to the other, was by no means over when I left the country in July, 1831, a couple of years after the shock.” Frances Milton Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans (London and New York, 1832), p. 282.

- Hall wrote in his original notes, “My Father does not remember Buonaparte. That he was there at the same time with him is certain, but most unfortunately his journal which had been kept day by day for some years before, stops a few weeks before he went to Brienne. My Father was not actually a student at the Military College; he was on a visit to the late Mr. Wm. Hamilton, who lived at the Château de Brienne. My father has an obscure recollection of some boy at the Military College having blown up one of the garden walls with gunpowder, but he does not recollect his name. The circumstance was brought to his recollection, and connected itself with Buonaparte at the time of his first rising into the notice, as a great military character. Whether or not he was the mischievous youth who demolished the wall is uncertain, but it would be an amusing question to put to Buonaparte himself.” Sophy Hall, Basil Hall, “The First Englishman Napoleon Ever Saw,” The Nineteenth Century and After, Vol. 72, No. X, Issue 428 (London, October 1912), p. 731.

- Basil Hall, Voyage to Loo-Choo, and Other Places in the Eastern Seas in the Year 1816 (Edinburgh, 1826), pp. 310-321.

- Basil Hall, Travels in India, Ceylon and Borneo, edited by H.G. Rawlinson (New Delhi, 1995), p. 12.

4 commments on “When Basil Hall Met Napoleon”

Join the discussion

Your father was the first Englishman I ever saw, and I have recollected him all my life on that account.

Napoleon Bonaparte

A fascinating article. Thank you.

Thanks, Dale. Glad you enjoyed it.

Shannon, it is remarkable how many such exchanges and conversations have been had throughout history but hundreds [yea thousands] have gone unrecorded and forgotten. This one is very interesting to read! Thanks! You have taken us back in a time machine!

You’re most welcome, Randall. Glad you liked the article!