Basil Hall was a British naval officer, traveller and author who wrote engaging books about his trips to Asia, South America and North America in the early 1800s. In 1817, Hall met with defeated French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte on the remote South Atlantic island of St. Helena. A dozen years later, Hall’s publication about his travels in the United States caused a “moral earthquake” among Americans. (1)

About Basil Hall

Captain Basil Hall, by Henry Raeburn

Basil Hall was born in Edinburgh on December 31, 1788. His father – Sir James Hall, the fourth Baronet of Dunglass – was a prominent Scottish geologist and geophysicist who later became a member of the British House of Commons. James Hall had visited Brienne, France, when Napoleon was a student at the military academy there, something that later came in handy for his son. Basil’s mother, Helen Douglas, was the daughter of the fourth Earl of Selkirk.

Basil Hall joined the Royal Navy at the age of 13. In 1808, he was commissioned as a lieutenant on the frigate HMS Endymion. As such, he helped British forces evacuate northern Spain at the Battle of Corunna in 1809. In 1812, Hall was sent to the East Indies Station, where he visited India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Borneo and Java. In 1816, he commanded HMS Lyra, a sloop-brig that served as escort on Lord Amherst’s diplomatic mission to China. Hall and his men undertook surveys of the west coast of Korea and the Loo-Choo (Ryukyu) Islands. On the return voyage to England in 1817, the Lyra called at St. Helena, where Napoleon had been imprisoned by the British since 1815.

Basil Hall’s visit with Napoleon

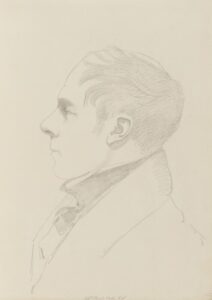

Napoleon Bonaparte at Saint Helena © The Trustees of the British Museum

At first Basil Hall tried to set up a meeting with Napoleon through St. Helena’s governor, Sir Hudson Lowe. As Napoleon was not on good terms with Lowe, that attempt came to nothing. Hall was then advised to go to Napoleon’s residence, Longwood House, in the hope that Napoleon might decide to see him on the spot. Once there, however, Hall was informed that Napoleon was not in the mood to see anybody. An approach through Napoleon’s “Grand Marshal of the Palace,” General Bertrand, also failed. Hall was finally able to secure an audience with the deposed French emperor by mentioning to Napoleon’s Irish physician, Barry O’Meara, that his father had been at Brienne while Napoleon was there. When O’Meara took this information to Napoleon, the latter agreed to see Hall.

The meeting took place in the afternoon of August 13, 1817, and lasted about 25 minutes. It was conducted in French, as Napoleon did not speak English. Later that day, Hall – who kept a daily journal – wrote down everything he could remember about the conversation. What follows is the account published in his book about his voyage to East Asia.

On Basil Hall’s father

“On entering the room, I saw Buonaparte standing before the fire, with his head leaning on his hand, and his elbow resting on the chimney-piece. He looked up, and came forward two paces, returning my salutation with a careless sort of bow, or nod. His first question was, ‘What is your name?’ and, upon my answering, he said, ‘Ah, – Hall – I knew your father when I was at the Military College of Brienne – I remember him perfectly – he was fond of mathematics – he did not associate much with the younger part of the scholars, but rather with the priests and professors, in another part of the town from that in which we lived.’ He then paused for an instant, and as he seemed to expect me to speak, I remarked that I had often heard my father mention the circumstance of his having been at Brienne during the period referred to; but had never supposed it possible that a private individual could be remembered at such a distance of time, the interval of which had been filled with so many important events. ‘Oh no,’ exclaimed he, ‘it is not in the least surprising; your father was the first Englishman I ever saw, and I have recollected him all my life on that account.’ (2) …

“Buonaparte asked, with a playful expression of countenance…. ‘Have you ever heard your father speak of me?’ I replied instantly, ‘Very often.’ Upon which he said, in a quick, sharp tone, ‘What does he say of me?’ … I said that I had often heard him express great admiration of the encouragement he had always given to science while he was Emperor of the French. He laughed and nodded repeatedly, as if gratified by what was said.

“His next question was, ‘Did you ever hear your father express any desire to see me?’ I replied that I had heard him often say there was no man alive so well worth seeing, and that he had strictly enjoined me to wait upon him if ever I should have an opportunity.’ ‘Very well,’ retorted Buonaparte, ‘if he really considers me such a curiosity, and is so desirous to see me, why does he not come to St. Helena for that purpose?’

“I was at first at a loss to know whether this question was put seriously or ironically; but as I saw him waiting for an answer, I said my father had too many occupations and duties to fix him at home. ‘Has he any public duties? Does he fill a public station?’ I told him, none of an official nature; but that he was President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the duties of which claimed a good deal of his time and attention. This observation gave rise to a series of inquiries respecting the constitution of the Society in question. He made me describe the duties of all the office-bearers, from the president to the secretary, and the manner in which scientific papers were brought before the society’s notice. He seemed much struck, I thought, and rather amused, with the custom of discussing subjects publicly at the meetings in Edinburgh. When I told him the number of members was several hundreds, he shook his head and said, ‘All these cannot surely be men of science!’

“When he had satisfied himself on this topic, he reverted to the subject of my father, and after seeming to make a calculation, observed, ‘Your father must, I think, be my senior by nine or ten years – at least nine – but I think ten. Tell me, is it not so?’ I answered that he was very nearly correct. Upon which he laughed and turned almost completely round on his heel, nodding his head several times. I did not presume to ask him where the joke lay, but imagined he was pleased with the correctness of his computation. He followed up his inquiries by begging to know what number of children my father had; and did not quit this branch of the subject till he had obtained a correct list of the ages and occupation of the whole family.

On Hall’s voyage to Asia

“He then asked, ‘How long were you in France?’ and on my saying I had not yet visited that country, he desired to know where I had learned French. I said, from Frenchmen on board various ships of war. ‘Were you the prisoner amongst the French,’ he asked, ‘or were they your prisoners?’ I told him my teachers were French officers captured by the ships I had served in. He then desired me to describe the details of the chase and capture of the ships we had made prize of; but soon seeing that this subject afforded no point of any interest, he cut it short by asking me about the Lyra’s voyage to the Eastern Seas, from which I was now returning. This topic proved a new and fertile source of interest, and he engaged in it, accordingly, with the most astonishing degree of eagerness. …

“Having settled where [Loo-Choo] lay, he cross-questioned me about the inhabitants with a closeness – I may call it a severity of investigation – which far exceeds everything I have met with in any other instance. His questions were not by any means put at random, but each one had some definite reference to that which preceded it or was about to follow. I felt in a short time so completely exposed to his view, that it would have been impossible to have concealed or qualified the smallest particular. Such, indeed, was the rapidity of his apprehension of the subjects which interested him, and the astonishing ease with which he arranged and generalized the few points of information I gave him, that he sometimes outstripped my narrative, saw the conclusion I was coming to before I spoke it, and fairly robbed me of my story.

“Several circumstances, however, respecting the Loo-Choo people, surprised even him a good deal; and I had the satisfaction of seeing him more than once completely perplexed, and unable to account for the phenomena which I related. Nothing struck him so much as their having no arms. ‘Point d’armes!’ he exclaimed, ‘c’est à dire point de cannons – ils ont des fusils?’ Not even muskets, I replied. ‘Eh bien donc – des lances, ou, au moins, des arcs et des flêches?’ I told him they had neither one nor other. ‘Ni poignards?’ cried he, with increasing vehemence. No, none. ‘Mais!’ said Buonaparte, clenching his fist, and raising his voice to a loud pitch, ‘Mais! sans armes, comment se bat-on?’ [But without weapons, how do they fight?]

“I could only reply, that as far as we had been able to discover, they had never had any wars, but remained in a state of internal and external peace. ‘No wars!’ cried he, with a scornful and incredulous expression, as if the existence of any people under the sun without wars was a monstrous anomaly.

“In like manner, but without being so much moved, he seemed to discredit the account I gave him of their having no money, and of their setting no value upon our silver or gold coins. After hearing these facts stated, be mused for some time, muttering to himself, in a low tone, ‘Not know the use of money – are careless about gold and silver.’ Then looking up, he asked, sharply, ‘How then did you contrive to pay these strangest of all people for the bullocks and other good things which they seem to have sent on board in such quantities?’ When I informed him that we could not prevail upon the people of Loo-Choo to receive payment of any kind, he expressed great surprise at their liberality, and made me repeat to him twice the list of things with which we were supplied by these hospitable islanders.

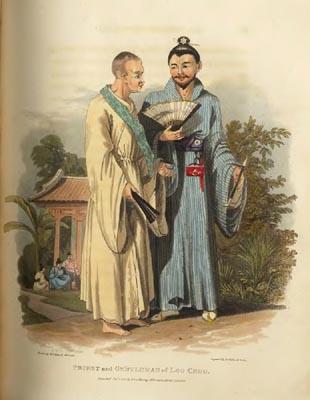

Korean Chief and his Secretary, from Basil Hall’s voyage

“I had carried with me, at Count Bertrand’s suggestion, some drawings of the scenery and costume of Loo-Choo and [K]orea, which I found of use in describing the inhabitants. When we were speaking of [K]orea, he took one of the drawings from me, and running his eye over the different parts, repeated to himself, ‘An old man with a very large hat, and long white beard, ha! – a long pipe in his hand – a Chinese mat – a Chinese dress – a man near him writing – all very good and distinctly drawn.’ He then required me to tell him where the different parts of these dresses were manufactured, and what were the different prices – questions I could not answer. He wished to be informed as to the state of agriculture in Loo-Choo – whether they ploughed with horses or bullocks – how they managed their crops, and whether or not their fields were irrigated like those in China, where, as he understood, the system of artificial watering was carried to a great extent. The climate, the aspect of the country, the structure of the houses and boats, the fashion of their dresses, even to the minutest particular in the formation of their straw sandals and tobacco pouches, occupied his attention. He appeared considerably amused at the pertinacity with which they kept their women out of our sight, but repeatedly expressed himself much pleased with Captain Maxwell’s moderation and good sense in forbearing to urge any point upon the natives which was disagreeable to them, or contrary to the laws of their country.

“He asked many questions respecting the religion of China and Loo-Choo, and appeared well aware of the striking resemblance between the appearance of the Catholic Priests and the Chinese Bonzes; a resemblance which, as he remarked, extends to many parts of the religious ceremonies of both. Here, however, as he also observed, the comparison stops; since the Bonzes of China exert no influence whatsoever over the minds of the people, and never interfere in their temporal or eternal concerns. In Loo-Choo, where everything else is so praiseworthy, the low state of the priesthood is as remarkable as in the neighbouring continent, an anomaly which Buonaparte dwelt upon for some time without coming to any satisfactory explanation.

Priest and Gentleman of Loo-Choo, from Basil Hall’s voyage

“With the exception of a momentary fit of scorn and incredulity when told that the Loo-Chooans had no wars or weapons of destruction, he was in high good humour while examining me on those topics. The cheerfulness, I may almost call it familiarity, with which he conversed, not only put me quite at ease in his presence, but made me repeatedly forget that respectful attention with which it was my duty, as well as my wish on every account, to treat the fallen monarch. The interest he took in topics which were then uppermost in my thoughts, was a natural source of fresh animation in my own case; and I was thrown off my guard, more than once, and unconsciously addressed him with an unwarrantable degree of freedom. When, however, I perceived my error, and of course checked myself, he good-humouredly encouraged me to go on in the same strain, in a manner so sincere and altogether so kindly, that I was in the next instant as much at my ease as before.

“‘What do these Loo-Choo friends of yours know of other countries?’ he asked. I told him they were acquainted only with China and Japan. ‘Yes, yes,’ continued he; ‘but of Europe? What do they know of us?’ I replied, ‘They know nothing of Europe at all; they know nothing about France or England; neither,’ I added, ‘have they ever heard of your Majesty.’ Buonaparte laughed heartily at this extraordinary particular in the history of Loo-Choo, a circumstance, he may well have thought, which distinguished it from every other corner of the known world. …

Back to Hall and his father

“When he had satisfied himself about our voyage, or at least had extracted everything I could tell him about it, he returned to the subject which had first occupied him, and said in an abrupt way, ‘Is your father an Edinburgh Reviewer?’ I answered, that the names of the authors of that work were kept secret, but that some of my father’s works had been criticised in the journal alluded to. Upon which he turned half round on his heel towards Bertrand, and nodding several times, said, with a significant smile, ‘Ha! ha!’ as if to imply his perfect knowledge of the distinction between author and critic.

“Buonaparte then said, ‘Are you married?’ and upon my replying in the negative, continued, ‘Why not? What is the reason you don’t marry?’ I was somewhat at a loss for a good answer, and remained silent. He repeated his question, however, in such a way that I was forced to say something, and told him I had been too busy all my life; besides which, I was not in circumstances to marry. He did not seem to understand me, and again wished to know why I was a bachelor. I told him I was too poor a man to marry. ‘Aha!’ he cried, ‘I now see – want of money – no money – yes, yes!’ and laughed heartily; in which I joined, of course, though to say the truth, I did not altogether see the humorous point of the joke.

“The last question he put related to the size and force of the vessel I commanded, and then he said, in a tone of authority, as if he had some influence in the matter, ‘You will reach England in thirty-five days’ – a prophecy, by the by, which failed miserably in the accomplishment, as we took sixty-two days, and were nearly starved into the bargain. After this remark he paused for about a quarter of a minute, and then making me a slight inclination of his head, wished me a good voyage, and stepping back a couple of paces, allowed me to retire. …

Hall’s impression of Napoleon

“Buonaparte struck me as differing considerably from the pictures and busts I had seen of him. His face and figure looked much broader and more square, larger, indeed, in every way, than any representation I had met with. His corpulency, at this time universally reported to be excessive, was by no means remarkable. His flesh looked, on the contrary, firm and muscular. There was not the least trace of colour in his cheeks; in fact, his skin was more like marble than ordinary flesh. Not the smallest trace of a wrinkle was discernible on his brow, nor an approach to a furrow on any part of his countenance. His health and spirits, judging from appearances, were excellent; though at this period it was generally believed in England that he was fast sinking under a complication of diseases, and that his spirits were entirely gone. His manner of speaking was rather slow than otherwise, and perfectly distinct: he waited with great patience and kindness for my answers to his questions, and a reference to Count Bertrand was necessary only once during the whole conversation. The brilliant and sometimes dazzling expression of his eye could not be overlooked. It was not, however, a permanent lustre, for it was only remarkable when he was excited by some point of particular interest. It is impossible to imagine an expression of more entire mildness, I may almost call it of benignity and kindliness, than that which played over his features during the whole interview. If, therefore, he were at this time out of health and in low spirits, his power of self command must have been even more extraordinary than is generally supposed; for his whole deportment, his conversation, and the expression of his countenance, indicated a frame in perfect health, and a mind at ease.” (3)

American criticism

Basil Hall by Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey, pencil, circa 1825-1830, NPG 316a(62) © National Portrait Gallery, London

Once back in England, Basil Hall was promoted to the rank of captain. In 1820, Hall was put in command of HMS Conway, a 26-gun frigate on the South American Station. From 1820-1822 he travelled along the coasts of Chile, Peru and Mexico on a mission to protect British interests in the newly independent Spanish colonies.

Hall retired from the navy in 1823. In 1825, he married Margaret Congalton Hunter (1799-1876), daughter of a former British consul in Spain. Hall and Margaret had one child, Elizabeth (Eliza) Jane.

In 1827, Hall sailed with his wife and daughter to North America, where they travelled around the United States and also visited Canada. Although written in his usual “good-natured, breezy, conscientious, observant manner,” Hall’s frank impressions, laid out in his book Travels in North America in the years 1827 and 1828, caused such an uproar in the United States that some booksellers refused to carry it. (You can read excerpts in my posts about Washington D.C. in the 1820s, John Quincy Adams and the White House Billiard Table, Visiting Niagara Falls in the Early 19th Century, and How did people shop in the early 1800s?.)

Hall was hurt by the American reception of his book and found it hard to understand the criticism.

In all my travels, both among heathens and among Christians, I have never encountered any people by whom I found it nearly so difficult to make myself understood as by the Americans. (4)

Basil Hall’s later life

Basil Hall in later years

In 1831, Basil Hall published the first of his 9-volume Fragments of Voyages and Travels, a description of naval life and adventure “written chiefly for young persons.” This was followed, in 1836, by Schloss Hainfield, or A Winter in Lower Styria, based on time he spent with Jane Cranstoun, the Countess of Purgstall. In 1841 he published Patchwork, a three-volume collection of tales from his travels in Europe.

Sadly, in 1842, Captain Basil Hall was confined as a mental patient at the Royal Naval Hospital Haslar in Portsmouth. He died there on September 11, 1844, at the age of 55.

The Hall-De Lancey Connection

Magdalene (Hall) De Lancey

In April 1815, Basil Hall’s sister Magdalene married American-born Colonel William Howe De Lancy, a friend of Basil’s who had served in the British Army under the Duke of Wellington in Spain. When Napoleon escaped from Elba in 1815, Wellington insisted on having De Lancey appointed as quartermaster general of the army in Belgium, instead of Hudson Lowe, whom Wellington disliked. (Lowe went on to marry De Lancey’s sister, Susan Johnson, and to become governor of St. Helena.)

Since Magdalene and De Lancey were still on their honeymoon, she joined her husband in Belgium. On June 18, 1815, while speaking with Wellington during the Battle of Waterloo, De Lancey was hit in the back by a ricocheting cannonball, which knocked him from his horse. Initial reports said he had died, but he was found alive in a peasant’s cottage, where Magdalene tenderly nursed him. Eight days later, he died of his injuries. At her brother’s request, Magdalene wrote an account of those final days. This was later published as A Week at Waterloo in 1815. Basil Hall shared the narrative with Sir Walter Scott and Charles Dickens, among others. They were very touched by it.

Basil Hall was a gifted writer with keen powers of observation. His books are available for free on the Internet Archive.

You might also enjoy:

When the Duke of Wellington Met Napoleon’s Wife

When Princess Caroline Met Empress Marie Louise

When Louisa Adams Met Joseph Bonaparte

When John Quincy Adams Met Madame de Staël

When an Englishman Met a Napoleonic Captain in Restoration France

- “Captain Basil Hall’s ‘Travels in North America’ [produced] a sort of moral earthquake and the vibration it occasioned through the nerves of the republic, from one corner of the Union to the other, was by no means over when I left the country in July, 1831, a couple of years after the shock.” Frances Milton Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans (London and New York, 1832), p. 282.

- Hall wrote in his original notes, “My Father does not remember Buonaparte. That he was there at the same time with him is certain, but most unfortunately his journal which had been kept day by day for some years before, stops a few weeks before he went to Brienne. My Father was not actually a student at the Military College; he was on a visit to the late Mr. Wm. Hamilton, who lived at the Château de Brienne. My father has an obscure recollection of some boy at the Military College having blown up one of the garden walls with gunpowder, but he does not recollect his name. The circumstance was brought to his recollection, and connected itself with Buonaparte at the time of his first rising into the notice, as a great military character. Whether or not he was the mischievous youth who demolished the wall is uncertain, but it would be an amusing question to put to Buonaparte himself.” Sophy Hall, Basil Hall, “The First Englishman Napoleon Ever Saw,” The Nineteenth Century and After, Vol. 72, No. X, Issue 428 (London, October 1912), p. 731.

- Basil Hall, Voyage to Loo-Choo, and Other Places in the Eastern Seas in the Year 1816 (Edinburgh, 1826), pp. 310-321.

- Basil Hall, Travels in India, Ceylon and Borneo, edited by H.G. Rawlinson (New Delhi, 1995), p. 12.

What did Napoleon want to achieve? This question is less about Napoleon’s goal in particular military campaigns than it is about his broader ambition. Did Napoleon have a lifelong aspiration or overarching aim? Was he pursuing a series of specific objectives? Or was he simply responding to circumstances, with no particular goal in mind?

Napoleon in his study, by Paul Delaroche

How might we know?

It can be hard to know what our own motivations are, let alone those of someone who died over 200 years ago. Napoleon talked about the difficulty of trying to determine one’s intentions. He said that, when writing about him, even people who worked with him would “have to state not so much what really existed, as what they believe to have existed; for which of them ever possessed the entire general conception of my mind? … However…they would have the advantage over me: for I should very frequently have found it most difficult to affirm confidently what had been my whole and entire thoughts on any given subject.” (1)

The task of deciphering Napoleon’s goals is complicated by the fact that he was a master of propaganda who played a prominent role in writing and editing his own story. From an early stage in his career, Napoleon used letters, military dispatches, and other means to exaggerate his triumphs and conceal – or blame others for – his failures. His writings and reported remarks are voluminous and contain many contradictions. During the final years of his life, when he was in exile on St. Helena, he dictated memoirs that portrayed his actions and intentions in the best possible light. He often tried to give a consistency to his aims that might not have been present at the time. This means that we cannot necessarily take Napoleon’s word for what he was trying to achieve, especially when that word came after the fact. We can, however, look at things that Napoleon said earlier in his life about his goals and ambition. We can also look at what some of the historians who have tried to answer this question have said.

Of course, a person’s goals tend to change over their lifetime. As certain goals are realized, or prove unattainable, others take their place. Napoleon had different goals at different stages of his life. This is easiest to see by taking a brief look at his career and what motivated him during each phase.

Napoleon’s goals in his youth

Napoleon Bonaparte at age 22 (illustration based on a portrait by Jean-Baptiste Greuze)

Historians do not know much about Napoleon’s childhood. Most anecdotes of Napoleon as a boy were recounted much later, in light of his subsequent fame. There is no record of Napoleon saying as a child what he wanted to do when he grew up. He was born in 1769 on Corsica, an island in the Mediterranean Sea that had recently come under French control. Corsica was a violent, pre-feudal society, in which ties of kinship overrode loyalty to king or country. Pagan myths co-existed with Christianity. There was a strong belief in destiny, which Napoleon absorbed.

When Napoleon was nine, he left Corsica to begin studies at a military school in Brienne, in northern France. There he learned about Alexander the Great, Hannibal, Julius Caesar, Charlemagne and other long-ago heroes who were meant to serve as role models for aspiring soldiers. It is reasonable to suppose that Napoleon, like many other boys of his generation, dreamed of emulating these heroes. He later said, “The reading of history very soon made me feel that I was capable of achieving as much as the men who are placed in the highest ranks of our annals, though I had no goal before me, and though my hopes went no further than my promotion to general.” (2)

By 1784, Napoleon wanted to go into the navy, but he had not completed the six years of study necessary to enter that branch of the armed forces. Instead, he joined the artillery. After a year of training at the military school in Paris, he was posted, at age 16, as an officer to the artillery regiment of La Fère, stationed at Valence in southeastern France.

Napoleon’s loyalties at this point were not to France, but to Corsica. He was an ardent supporter of Pasquale Paoli, the leader of Corsican resistance to French rule. Between 1786 and 1793, Napoleon took five long leaves of absence from his regiment to spend time on Corsica, where he dealt with family matters and became involved in local politics. Although Napoleon supported the French Revolution, his writings during this period displayed a strong dislike of Frenchmen, whom he considered the oppressors of his people.

He also wrote approvingly of those who put love of country ahead of love of acclaim. In an essay drafted in 1787, Napoleon praised Leonidas, king of the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta, who died attempting to defend Greece against a much larger Persian force.

Our souls are undoubtedly deeply moved when we hear of the deeds of Philip, Alexander, Charlemagne, Turenne, Condé, Machiavelli and so many other illustrious men who, in their heroic careers, were guided by the esteem of men; but what feeling controls our souls at the sight of Leonidas and his three hundred Spartans. They did not go to battle, they went to their deaths for the fate that threatened their homeland…. [L]ove of glory could not have been the driving force behind the Spartans. (3)

In the same essay, Napoleon commended Themistocles – an Athenian politician and general who had been compelled to flee Greece and went to work for the Persian king – for allegedly committing suicide rather than following the king’s orders to make war against Athens.

Themistocles preferred to drink of the fatal cup rather than to see himself at the head of the Oriental troops and to be within reach of avenging his particular outrage. He could undoubtedly have hoped to subjugate Greece. What glory he would have had in posterity, and what satisfaction for his ambition! But no, he lived in the midst of the splendours of Persia, always missing his country. ‘O my son, we would perish if we had not perished!’ – an energetic phrase that should remain forever written in the heart of a true patriot. (4)

In 1792, through the support of the Bonaparte clan and allied families, Napoleon got himself elected as a lieutenant colonel in the Corsican National Guard. This would allow him to remain on Corsica without losing his army commission. However, in 1793 the Bonaparte family had a falling out with Paoli. They fled to the French mainland. Only then, at the age of 23, did Napoleon conclude that his future lay in France, rather than in Corsica. He abandoned his support for Corsican independence and embraced the Frenchmen he had previously criticized not out of love for France, but because he and his family hoped to find more favourable circumstances there.

Napoleon’s early goals in France

In France, Napoleon advanced his career through his skill as a soldier, his use of political connections, and his good fortune to be in the right place at the right time. France was at war with Austria, Prussia, Great Britain and other neighbouring monarchies. There were counter-revolutionary uprisings within the country, as well as fighting between the Girondin (moderate) and Montagnard (radical) factions of the republican government. The Revolutionary purge of nobles from the French army had resulted in a shortage of experienced officers. This meant that talented young men like Napoleon could easily move up the ranks.

Thanks to the support of a Corsican deputy to the National Convention, Napoleon was given command of the French artillery at the siege of Toulon. This port city on France’s Mediterranean coast was under the control of royalist rebels, supported by an Anglo-Spanish fleet. Napoleon played a key role in recapturing the port. As a result, in December 1793 he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general.

One of Napoleon’s strongest supporters in the National Convention was Augustin Robespierre, the younger brother of Maximilien Robespierre, leader of the Montagnards and a member of the governing Committee of Public Safety, which oversaw the Reign of Terror. Shortly after the arrest and execution of the Robespierres and their allies in 1794, Napoleon was arrested because of his association with Augustin. He spent ten days as a prisoner before being released. This put an end to his embrace of radicalism, or any other ideology.

Now out of political favour, Napoleon found his career stalled. In May 1795, he was ordered to join the Army of the West, which was fighting royalist rebels in the Vendée area of western France. He would have to accept command of an infantry brigade, rather than the artillery, so he went to Paris to see if he could obtain something better. On the way there he met Victorine de Chastenay, a young aristocrat, who spoke to him for hours. She wrote, “I soon discovered that the republican general had no republican principles or beliefs. I was surprised, but his frankness was complete in this respect. … I think Bonaparte would have emigrated, if emigration had indeed offered any chance of success.” (5)

Because of his refusal to take up his post, Napoleon was removed from regular army service and put on half pay. Although he didn’t want to serve in the Vendée, he retained the goal of becoming a military hero. In August 1795, he wrote to his brother Joseph, “I only want to find myself on the battlefield, a soldier must either win laurels or perish gloriously.” (6) He applied to go to Turkey to modernize the artillery of the Ottoman sultan. Instead, he was given a desk job in the Topographical Bureau of the Committee of Public Safety.

Luck came to Napoleon’s rescue. In October 1795, the government was threatened by uprisings in Paris. Paul Barras, a politician tasked with defence of the Tuileries Palace (seat of the National Convention), called on discharged officers to come to the Convention’s aid. Napoleon was among those who seized the opportunity to be reinstated in the army. Barras put him in charge of the artillery. When the insurgents tried to attack the Tuileries, Napoleon gave orders to fire, dispersing the mob.

Barras became a member of the new governing Directory of France. He recommended that Napoleon be appointed commander of the Army of the Interior, responsible for maintaining law and order in Paris and the surrounding area. This was a big promotion. It gave Napoleon prominence, influence and money, which he showered on his family. But it did not put him on a battlefield. Napoleon had long been interested in the war on the Italian front. Now he badgered the Directory with criticisms of how the Italian campaign was being fought and ideas for how it could be won. In March 1796 (the same month Napoleon married Josephine), the Directory gave him command of the Army of Italy, despite his very limited military experience.

The effect of Italy

Napoleon giving orders at the Battle of Lodi, by Louis-François Lejeune

It was in Italy that Napoleon’s career took off. He assumed control of an army that was in bad shape, turned it into a capable fighting force, defeated Sardinian, Austrian and other troops, and secured peace treaties that left only Britain remaining in the war against France. While doing so, he ran a propaganda campaign that inflated his achievements, hid his losses, and put him in the public spotlight in France.

Italy is where Napoleon fused his thirst for military glory with a desire for political power. He later said, “the moment in which I became conscious of the difference there existed between other men and myself, and when I had a glimpse of the fact that I was called on to settle the affairs of France, was several days after the Battle of Lodi [May 10, 1796].” (7) He had received instructions from the Directory to divide his army in two, march towards Naples with the larger part, and leave the remainder under the command of another general. Napoleon considered this a “senseless order,” so he refused to comply.

From this precise moment dates my conception of my own superiority. I felt that I was worth much more and was much stronger than the Government that had seen fit to issue such an order; that I was better fitted than it was to govern; and that the Government was not only incapable, but also lacking in judgment on matters that were so important as ultimately to endanger France. I felt that I was destined to save France. (8)

By politically exploiting his victories, and sending back to France a portion of what he extracted financially from the Italians, Napoleon was able to break free of the Directory’s control. He took over the direction of French policy in Italy. He administered the territories his troops occupied. He conducted diplomatic negotiations. He created Italian client states. He became wealthy. In 1797, he told a French diplomat, “[In Italy] I am…more of a sovereign than commander of an army. … I have tasted command, and I cannot give it up.” (9)

In October 1797, the Directory rewarded Napoleon by naming him commander of the Army of England, a position that they hoped would keep him busy and away from Paris. With both military force and public opinion at his disposal, he was a rival to those in power.

Napoleon’s goals in Egypt

Napoleon in Egypt, by Édouard Detaille

Napoleon started to plan an invasion of England, but after inspecting ports along the English Channel in early 1798, he concluded that it would be foolish to launch an assault given the weakness of the French navy. Instead he proposed invading Egypt, which was something he and the French foreign minister, Talleyrand, had been thinking about for months. Egypt was part of the crumbling Ottoman Empire and under the control of local Mamelukes. Gaining Egypt could make up for the loss of French colonies in the Americas, disrupt British trade and expand French markets, and open the door to French intervention in India. In August 1797, Napoleon had written to the Directory, “The time is not far off when we will think that, to truly destroy England, we must seize Egypt. The approaching death of the vast Ottoman Empire forces us to think ahead about taking measures to preserve our trade in the Levant.” (10)

Napoleon may also have had a personal motive for wanting to conquer Egypt. According to biographer Frank McLynn:

After three months in Paris, he was ceasing to be an object of universal fascination. Convinced of the need for ceaseless momentum, he knew he had either to attempt a coup in Paris or find an adventure elsewhere. He felt he would probably lose if he attempted an invasion of England, but would probably win if he went to Egypt. (11)

In April 1798, the Directors ordered the formation of an Army of the Orient, with Napoleon as commander in chief. They instructed him to take possession of Egypt, drive the British from the Middle East, construct a canal across the Isthmus of Suez, and ensure French possession of the Red Sea.

Napoleon and his expedition, which included scientists and scholars as well as soldiers, arrived in Egypt at the beginning of July. The French were hampered by intense heat, shortages of food and water, and hostile Bedouins, but they won the Battle of the Pyramids and occupied Cairo. Napoleon wrote to his brother Joseph that he might be in back in France in two months. Then, at the beginning of August, the French fleet in Egypt was destroyed by the British Navy at the Battle of the Nile. This left Napoleon and his army isolated, with the Mediterranean under British control. Still, Napoleon did not anticipate a long stay in Egypt. In September, he wrote to the Directory: “I will not be able to be back in Paris in October, as I promised you; but it will only take me a few months.” (12)

In February 1799, Napoleon took most of his army on a gruelling march across the desert to attack Ottoman forces that were gathering in Syria. He made it as far as Acre, but was unable to prevail against the Ottoman defenders, who were reinforced by the British, so he retreated to Egypt. Over one-third of his men were dead, ill or wounded. In July, he gained a victory over an Ottoman army in the Battle of Aboukir.

In August, Napoleon learned that the Directory was in a vulnerable position. France was threatened by a new coalition of England, Austria, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Naples and Portugal. The allies had defeated French offensives in Germany and Switzerland, invaded Holland, and undone Napoleon’s gains in northern Italy. There were revolts in France and rumours of an impending coup. He decided to abandon his army in Egypt and return to France. He landed at the beginning of October, just after the arrival of news of his victory at Aboukir. Although the Egyptian campaign had done little to advance French interests (the Army of the Orient surrendered to the British in 1801), it clearly helped Napoleon’s. His propaganda efforts, and those of his family and friends, portrayed Egypt as a triumph, and his decision to return as motivated by the desire to be where he could be most useful. He was welcomed as a hero.

Coup of 18 Brumaire

Napoleon Bonaparte in the coup d’état of 18 Brumaire, by François Bouchot, 1840

Napoleon’s goal at this point was to gain political power in France. This was something he had developed a taste for in Italy. His experience governing Egypt had reinforced it. Napoleon sounded out the possibility of becoming a member of the Directory, but he did not meet the minimum age requirement of 40. So he joined a group of conspirators who were plotting to overthrow the government. The coup was intended to be a civilian one (two of the plotters were Directors), but the civilians needed a military man who could back them up with force if necessary. Napoleon was not their first choice, but he was keen, available and popular.

The coup took place on November 9-10, 1799. It is known as the Coup of 18 Brumaire because that was the name for November 9 in the French Republican calendar. The coup was poorly planned and poorly executed. The French legislature, composed of the Council of Ancients and the Council of Five Hundred, did not play along as desired. Napoleon impatiently stormed into their sessions at the Château de Saint-Cloud. When Napoleon appeared uncertain of what to do after being assaulted by deputies in the Council of Five Hundred, his brother Lucien, who was President of the Five Hundred, saved the day by calling on soldiers to expel the deputies. There was a scuffle between soldiers and deputies, but no one was killed and there was no popular uprising against the coup. In the end, the Directory was dissolved and replaced by a provisional government led by three consuls, one of whom was Napoleon.

Now Napoleon manoeuvred to concentrate power in his hands. He proposed a draft constitution that gave all real executive authority to a First Consul, advised by two other consuls, and left a much weakened and divided legislative branch. That constitution was adopted in December. Napoleon became First Consul. To add the appearance of legitimacy to what was, in effect, a military coup, the public was asked to vote in a non-binding plebiscite on whether to accept the new constitution. There was no secret ballot; more than two-thirds of those eligible to vote did not do so; and Napoleon’s brother Lucien, who was the new Minister of the Interior, added thousands of extra ‘yes’ votes, with the result that over 99% of voters appeared to be in favour of the new constitution.

From Consulate to Empire

When Napoleon became First Consul, he was 30 years old. Up to this moment in his life he had no single, overriding goal. His rise to power was very much a family affair, and he wanted to ensure that members of his family were provided with money and influential positions. He may have held an idealistic view of a heroic personal destiny. Like many other officers of his generation, he wanted glory on the battlefield as well as political influence. He had flirted with Corsican nationalism and radical republicanism, but abandoned both. He went to Italy and Egypt because of circumstances, rather than an overriding desire to be there.

Now that Napoleon was at the head of the French government, his goals were to stabilize France, strengthen his power and provide security for his position. He attracted able men to his government and launched a series of reforms that reduced political factionalism, improved public finances and centralized public administration. He oversaw the codification of a new system of law, a project that had been underway since the early years of the French Revolution. He ended the Revolutionary breach with the Catholic Church and tried to end the war in the Vendée. He also led a successful military campaign against Austria, and secured peace treaties with Austria, Russia, Britain and the Ottoman Empire. This meant that by the end of June 1802 France was at peace. On August 2, 1802, a national referendum was held to ratify a new constitution that made Napoleon “First Consul for Life.” Again, there was no secret ballot, and only about half of those eligible voted. The official results showed over 99% in favour.

Napoleon presented his goals as being identical to those of France. When he was in exile on St. Helena he said, “I had no ambition distinct from [France’s] – that of her glory, her ascendancy, her majesty. … I…identified myself completely with her destinies. … Was I ever seen occupied about my personal interests?” (13)

However, Napoleon’s reforms secured the primary social and material gains of the Revolution at the expense of political liberty. He suppressed the press and undermined the independence of the legislature. He created a strong and efficient authoritarian state, ruled firmly from the top. Napoleon set himself up as the embodiment of France, which was a far cry from the republican principle of impersonal government. Regarding the limitations he introduced on liberty, Napoleon told one of his advisors: “At home and abroad, I reign only through the fear I inspire. If I were to abandon this system, I would soon be dethroned. This is my position and the motives for my conduct.” (14)

As evidenced by the referendums, legitimacy was another goal pursued by Napoleon. He wanted to be regarded as the rightful ruler of France and as the equal of other European monarchs, rather than a usurper. On May 18, 1804, Napoleon’s hand-picked Senate proclaimed him the hereditary “Emperor of the French.” It was not solely Napoleon’s personal ambition that led to this outcome. A constitutional hereditary monarchy was the preferred form of government of many French conservatives and moderates. It would also protect the benefits that the bourgeoisie and peasants had gained from the Revolution. Even if Napoleon were assassinated or killed in battle, his regime and reforms would continue to exist. A national plebiscite was held to confirm Napoleon’s change in status. The doctored results indicated 99.9% support. Half of the potential voters abstained. On December 2, 1804, Napoleon was crowned Emperor.

Imperial expansion

Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz, by François Gérard

By this time, the peace with Britain was over. Britain had been prepared to recognize France’s “natural frontiers” (bordered by the Pyrenees, the Alps and the Rhine), but Napoleon had used the interlude to keep French troops in Holland, send French troops into Switzerland, reshuffle German territory, and annex Italian territory. He also sent an expedition to attempt to regain control over Saint-Domingue (Haiti). When this failed, he sold the Louisiana Territory to the United States and focused his goals on Europe.

In May 1803, Britain declared war on France. Napoleon prepared to invade Britain. He assembled an army on the coast of France and was gathering naval resources, but he lost most of his fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar in October 1805. Meanwhile, Austria and Russia had joined the war against France, so Napoleon took his assembled army and marched east, where he achieved victory in the Ulm campaign and the Battle of Austerlitz.

In 1806-07, Napoleon established the Confederation of the Rhine, occupied Prussia, defeated Russian forces, and won a peace that gave him additional territory, which he molded into a new Kingdom of Westphalia and a Polish client state called the Duchy of Warsaw. France was now the dominant power in Western Europe.

Britain remained at war with France, and Napoleon conducted economic warfare against her through his Continental System. In 1807, he invaded Britain’s ally, Portugal. In 1808, he invaded Spain. In 1809, he was back at war with Austria. After a six month campaign, Austria was defeated and became a French ally.

One of Napoleon’s consistent goals throughout this period was his desire to enrich and advance his family. From the time the Bonapartes left Corsica, Napoleon provided for them, found places for them, and promoted them. After he became Emperor, he appointed his stepson Eugène de Beauharnais viceroy of Italy. Louis Bonaparte became King of Holland. Joseph Bonaparte became the monarch of Naples, and later Spain. Caroline Bonaparte and her husband Joachim Murat received the Grand Duchy of Berg, before succeeding Joseph in Naples. Jérôme Bonaparte became King of Westphalia. Elisa Bonaparte presided over Tuscany.

Napoleon also wanted to have a son who could succeed him on the French throne. In 1809 he ended his marriage to Josephine, who had produced no children during their 13 years together. “I explained to her that unless I had a child, my dynasty was without any foundation.” (15) In 1810, Napoleon married Marie Louise, an Austrian archduchess. He hoped that this would solidify his alliance with Austria and provide his regime with further legitimacy, in addition to producing offspring. Their son, Napoleon II, was born on March 20, 1811.

In 1812, Napoleon embarked on a disastrous invasion of Russia, from which he had to retreat with the loss of over half a million men. In 1813-14, after subsequent defeats in Portugal and Spain, the Napoleonic empire collapsed. The allies drove Napoleon and his army back to France. He had to abdicate the French throne and submit to exile on Elba.

By 1813, any convergence between Napoleon’s goals and the interests of France had been lost. The pace of internal reform slowed after 1804 because Napoleon was preoccupied with war. His rule became increasingly autocratic. The insatiable demand for men and money to feed the perpetual fighting took a high toll. France’s European territory was larger in 1799, when Napoleon came to power, than it was at the end of his reign.

Historians have suggested that if Napoleon had been willing to accept peace on the basis of France’s natural frontiers, he could have remained in power and spared France the further loss of lives. However, “Napoleon was not ready to face the loss of prestige involved in the sacrifice of the ‘Grand Empire.’ The critical attitude of the Legislature at the beginning of 1813 convinced him that it would also mean the end of his autocracy in France.” (16)

The Hundred Days

In 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba and returned to France to again seize the throne. In doing so, Napoleon was motivated by self-interest. The French government was not paying him the annual stipend he had been promised; he feared that he might be deported to a more remote location; and he was worried that the Duke of Orleans would seize power in France and prove to be popular. The allies, of course, opposed Napoleon’s return. Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo and exiled to the remote South Atlantic island of St. Helena, where he died in 1821.

Thanks to Napoleon’s escapade, the Treaty of Paris (1815), which formally ended the Napoleonic Wars, imposed further exactions on France.

Viewed purely in terms of its territorial extent, the shape of France immediately after the Vienna Congress represented the total obliteration of everything Napoleon had ever achieved by conquest. All that physically remained of his famous exploits on the battlefield were the monumental buildings, the heroic sculptures, the triumphant paintings, and the other public emblems of his former glory. But was it really for this that over 900,000 Frenchmen, victims of the land wars of the Empire, had ultimately fought and died? On top of its harsh territorial provisions, the second Peace of Paris imposed a war indemnity of 700 million francs on France, to be settled within five years, and pending its payment an Allied army of occupation of 150,000 men was to be maintained on her northern and eastern frontiers. … By the end of 1815, the reality of ‘la gloire’ cast a very dim light in France, which makes its brilliant incandescence in the later Napoleonic legend seem all the more remarkable. (17)

Napoleon could have stayed on Elba and spared France this additional pain, but that would have required restraint, which was “totally out of tune with Napoleon’s character and ambition.” (18)

Napoleon’s ambition

Napoleon in his coronation robes, by François Gérard, 1805

Ambition is a word that appears repeatedly in conjunction with Napoleon. Ambition can be defined as “an ardent desire for rank, fame, or power” (Merriam-Webster), or “a strong desire for success, achievement, power, or wealth” (Cambridge Dictionary). In Napoleon’s time, ambition was defined as an “[i]mmoderate desire for honor, glory, elevation, distinction.” Ambition could also been viewed in a positive light, if qualified by adjectives such as noble or laudable, or used in a phrase like, “The prince’s only ambition is to make his people happy.” (19)

What was the nature of Napoleon’s ambition?

Napoleon’s brothers suggested that his ambition consisted primarily in advancing his own interest, rather than the interests of others. In 1792, Lucien wrote to Joseph, “I have always detected in Napoleon an ambition that is not altogether selfish, but that surpasses his love for the public good…. He seems to me well inclined to be a tyrant, and I believe that he would be one if he were king, and that his name would be a name of horror to posterity and to the sensible patriot.” (20)

Joseph later recalled that Napoleon, as a young man on Corsica, “had in mind the judgment of posterity; his heart palpitated at the idea of a great and noble deed that posterity would appreciate.” Napoleon said that he would like to be among those witnessing a representation of this deed after his death, “and read what a poet like the great Corneille would make [him] feel, think and say.” (21)

Josephine also thought that Napoleon’s ambition was focused on himself. When there were rumours that Napoleon had died in Egypt, she told Paul Barras, “He is the most ingrained and ferocious egotist that the earth has ever seen. He has never known anything but his interest, his ambition.” (22)

Napoleon’s own words regarding his ambition were inconsistent. In 1804, he said:

I have no ambition…or, if I do, it is so natural to me, so innate, so much a part of my existence, that it is like the blood that flows through my veins, like the air I breathe. It does not make me go any faster, or any differently, than the natural motives within me. I never have to fight either for it or against it. Ambition is never in a greater hurry than I am; it only keeps pace with the circumstances and my general way of thinking. (23)

In 1816, when he was in exile on St. Helena, Napoleon admitted that he had been ambitious, but gave it an unselfish cast.

Shall I be blamed for my ambition? This passion I must doubtless be allowed to have possessed, and that in no small degree; but, at the same time, my ambition was of the highest and noblest kind that ever, perhaps, existed!… That of establishing and of consecrating the Empire of reason, and the full exercise and complete enjoyment of all the human faculties! (24)

This was clearly said with an eye on the history books. Six months later, Napoleon said:

I never was truly my own master; but was always controlled by circumstance. Thus, at the commencement of my rise, during the Consulate, my sincere friends and warm partisans frequently asked me…what point was I driving at? and I always answered that I did not know. … Subsequently, during the Empire…many faces seemed to put the same question to me; and I might still have given the same reply. In fact, I was not master of my actions, because I was not fool enough to attempt to twist events into conformity with my system. On the contrary, I moulded my system according to the unforeseen succession of events. This often appeared like unsteadiness and inconsistency, and of these faults I was sometimes unjustly accused. (25)

However he perceived or coloured it, Napoleon clearly had ambition and acted in accordance with that ambition. He did not sit back and wait patiently for things to be offered to him. He sought out opportunities to advance his and his family’s interests and he made the most of them. He could have remained a general, focused on military objectives, but he chose to seek political power. When he obtained political power, he could have established a truly republican system, but he chose to establish an authoritarian one. He could have confined himself to fighting the wars he inherited, but he started new ones by invading Portugal, Spain and Russia.

Napoleon’s ambition was not for France, or for its citizens’ aspirations, or for an ideology, it was for his own personal aggrandizement. He had a large ego, he wanted power and glory, and he wanted to be remembered as a great man in history. On St. Helena, he said, “Had I succeeded, I should have died with the reputation of the greatest man that ever existed. As it is, although I have failed, I shall be considered as an extraordinary man. … From nothing I raised myself to be the most powerful monarch in the world. Europe was at my feet. My ambition was great, I admit, but it was of a cold nature, and caused by events, and the opinion of great bodies.” (26) Two months before he died, he said, “In five hundred years’ time, French imaginations will be full of me. They will talk only of the glory of our brilliant campaigns. Heaven help anyone who dares speak ill of me!” (27)

Sometimes Napoleon couched his ambition in language about destiny. The author J. Christopher Herold, who tried to decipher Napoleon’s thought, observed: “The salient characteristic of all of Napoleon’s utterances, on any subject whatsoever…is that by some twist he invariably ends by placing himself at the center. The destiny of General Bonaparte, the destiny of France, the destiny of Europe, the destiny of civilization – each was, in the last analysis, merely one aspect of the same thing.” (28) Herold concluded, “Fear of oblivion was also Napoleon’s motive.” (29)

Historian Geoffrey Ellis wrote, “In [Napoleon’s] view destiny came only to those few who were preordained for it, those marked out for special greatness, and capable of changing the course of history. As such, it was a noble call which had to be carried out, in his case through conquest, power, and personal glory.” (30)

According to historian Philip Dwyer, “In his mind, he was the tool of destiny; he felt he was driven towards a goal that he did not know, but that it involved changing the face of the world.” (31)

Biographer Frank McLynn boiled Napoleon’s ambition down to “a basic lust for power.” (32) And historian Adam Zamoyski contends that Napoleon’s “ambition [was] no greater than that of contemporaries such as Alexander I of Russia, Wellington, Nelson, Metternich, Blücher, Bernadotte and many more. What made his ambition so exceptional was the scope it was accorded by circumstance.” (33)

An opportunist

In search of power and glory, Napoleon was an improviser. His ambition looked for an outlet and he made the most of whatever opportunities came up. He said that he “frequently floated at the caprice of chance.”

I did not strive to subject circumstances to my ideas;…I in general suffered myself on the contrary to be led by them; and who can calculate beforehand the chances of accidental circumstances or unexpected events? I have, therefore, often found it necessary to alter essentially my plan of proceeding, and have acted through life upon general principles, rather than according to fixed plans. (34)

McLynn wrote that “Napoleon’s Achilles’ heel” was his “inability to concentrate on a single clear objective to the exclusion of all others.” (35) Ellis observed: “What made Napoleonic imperialism possible was its gradualism, and its course was determined by the chronology of war. Such empirical evidence suggests that Napoleon’s ambition was not driven by any over-arching ‘master plan’ or ‘grand design,’ present from the start and systematically worked out, but that it grew by an evolving process of pragmatic opportunism which eventually over-reached itself.” (36)

Philip Dwyer argued:

[H]is foreign policy was continually renewed and dictated entirely by circumstances and their immediate needs. Napoleon had in fact no coherent imperial foreign policy. Some historians have insisted that he conquered for the sake of conquering, with no defining goals and no overriding, consistent or specific long-term strategic objectives. Since each campaign created new enemies, the wars were continuous and could stop only with the defeat of Napoleon. (37)

Conclusion

Napoleon had no overarching aim, beyond a general desire for power and lasting fame, and the wish to advance his family along with himself. He had many shifting short-term goals, driven by a character that couldn’t be still and the ambition to make himself a great man. He seized power in France and conquered a large part of Western Europe thanks to his skilful pursuit of the opportunities afforded to his ambition. However, without a clear long-term objective, he was unable to set limits on his ambition and make the concessions to his adversaries that might have allowed him to remain in power. My novel, Napoleon in America, explores what might have happened if he had wound up in the United States.

You might also enjoy:

10 Interesting Facts About Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon at the Pyramids: Myth versus Fact

Why didn’t Napoleon escape to the United States?

Living Descendants of Napoleon and the Bonapartes

- Emmanuel de Las Cases, Memorial de Sainte Hélène: Journal of the Private Life and Conversations of the Emperor Napoleon at Saint Helena, Vol. IV, Part 7 (London, 1823), pp. 256-256.

- Jean Hanoteau (ed.), With Napoleon in Russia: The Memoirs of General de Caulaincourt, Duke of Vicenza, (New York, 1935), pp. 354-355.

- Frédéric Masson and Guido Biagi, Napoléon inconnu: Papiers inédits (1786-1793), Vol. I (Paris, 1895), pp. 186-187.

- Ibid., p. 188.

- Victorine de Chastenay, Mémoires de Madame de Chastenay, 1771-1815, Vol. I (Paris, 1896), pp. 282-283.

- The Confidential Correspondence of Napoleon Bonaparte with His Brother Joseph, Vol. I (New York, 1856), pp. 21-22.

- Henri-Gatien Bertrand, Napoleon at St. Helena: The Journals of General Bertrand from January to May of 1821, deciphered and annotated by Paul Fleuriot de Langle, translated by Frances Hume (Garden City, 1952), p. 91.

- Ibid., p. 92.

- André François Miot de Mélito, Memoirs of Count Miot de Melito, edited by General Fleischmann, translated by Mrs. Cashel Hoey and John Lillie, (New York, 1881), p. 113.

- Correspondance de Napoléon Ier, Vol. III (Paris, 1859), p. 311.

- Frank McLynn, Napoleon: A Biography (London, 1997), p. 169.

- Correspondance de Napoléon Ier, Vol. IV (Paris, 1860), p. 475.

- Las Cases, Memorial de Sainte Hélène, Vol. I, Part 2, pp. 309-310.

- Jean-Antoine Chaptal, Mes souvenirs sur Napoléon (Paris, 1893), p. 219.

- Bertrand, Napoleon at St. Helena, p. 56.

- Felix Markham, Napoleon (New York, 1963), p. 202.

- Geoffrey Ellis, Napoleon (London, 1997), pp. 233-234.

- Markham, Napoleon, p. 108.

- Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, Vol. I (Paris, 1798), p. 49.

- Frédéric Masson and Guido Biagi, Napoléon inconnu: Papiers inédits (1786-1793), Vol. II (Paris, 1895), p. 397.

- Mémoires et Correspondance Politique et Militaire du Roi Joseph, Vol. I (Paris, 1855), p. 38.

- Paul Barras, Memoirs of Barras, member of the Directorate, Vol. III, edited by George Duruy, translated by C.E. Roche (New York, 1896), p. 445.

- Pierre-Louis Roederer, Oeuvres du Comte P.L. Roederer publiées par son fils le Baron A.M. Roederer, Vol. III (Paris, 1854), p. 495.

- Las Cases, Memorial de Sainte Hélène, Vol. II, Part 3, pp. 197-198.

- Las Cases, Memorial de Sainte Hélène, Vol. IV, Part 7, pp. 133-134.

- Barry Edward O’Meara, Napoleon in Exile; or, A Voice from St. Helena, Vol. 1 (London, 1822), p. 405.

- Bertrand, Napoleon at St. Helena, 112.

- Christopher Herold, The Mind of Napoleon: A Selection from His Written and Spoken Words (New York, 1955), pp. xxviii-xxix.

- Ibid., p. xxxiii.

- Ellis, Napoleon, p.

- Philip Dwyer, Citizen Emperor: Napoleon in Power 1799-1815 (London, 2014), p. 348.

- McLynn, Napoleon: A Biography, p. 431.

- Adam Zamoyski, Napoleon: The Man Behind the Myth, eBook (London, 2018), Preface.

- Las Cases, Memorial de Sainte Hélène, Vol. IV, Part 7, p. 256.

- McLynn, Napoleon: A Biography, p. 326.

- Ellis, Napoleon, pp. 6-7.

- Dwyer, Citizen Emperor, 348.

Leopold I of Belgium began life as a minor German prince. He served as a Russian general against Napoleon, married into the British and French royal families, and was offered two separate crowns of his own. As the first king of the Belgians, Leopold consolidated Belgium’s independence and ensured that Belgium’s interests were considered by the great powers. He was also the uncle of both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

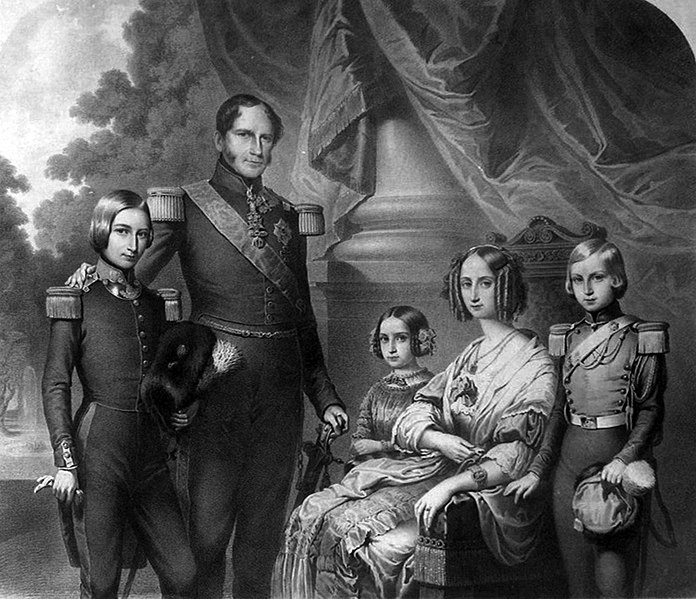

Leopold I, King of the Belgians, by Nicaise de Keyser, 1856

Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld

Leopold was born on December 16, 1790 in Coburg, Germany. At the time, Germany did not exist as a country. It was made up of many small territories, most of which were part of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by Austria. Coburg was in the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. Leopold’s grandfather was the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld and Leopold’s father, Francis, was heir to the duchy. Francis and his wife, Countess Augusta of Reuss-Ebersdorf, had seven children who survived to adulthood. Leopold was their youngest. He was named after Leopold II, the Holy Roman Emperor.

When Leopold was two years old, the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld became caught up in the wars between Revolutionary France and its neighbours. Leopold’s father – a bookish art connoisseur – was commissioned into the Austrian army. A number of French emigrants and noble families from the Rhine and Westphalia fled to Coburg for refuge. This exhausted the resources of the little duchy, which was already heavily indebted.

Despite their impoverished circumstances, the Coburgs were able to secure an important dynastic match. In 1795, a Russian general in search of a bride for Grand Duke Constantine (grandson of Empress Catherine the Great) fell ill and had to stop in Coburg. While there, he was charmed by Leopold’s three oldest sisters. When Empress Catherine invited the girls and their mother to St. Petersburg, Leopold went along. In February 1796, Leopold’s sister Juliana (who took the Russian name of Anna Feodorovna) married Grand Duke Constantine. The marriage did not last. Constantine treated Juliana cruelly and in 1801 she left him for good.

In the meantime, young Leopold became a member of the Russian Imperial Guard. He started as a captain in an infantry regiment, was transferred to a horse regiment as a colonel, and, at the age of 12, became a major general. These were honorary appointments and Leopold did not spend the whole time in Russia, but they were important to his later military career.

In 1800, Leopold’s grandfather died and Leopold’s father became the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. Leopold later wrote:

My poor father, whose health had been shattered early, was a most lovable character…. He was passionately fond of the arts and sciences. My beloved mother…had a warm heart and a fine intellect…. Without wishing to say anything against the other branches of the house of Saxony, ours was certainly the most intellectual. (1)

Leopold inherited his parents’ love of learning. He studied Christianity, Latin, ethics, logic, history, and the law of nations. In addition to his native German, he mastered French, English, Italian and Russian; he could later manage in Spanish and Flemish as well. He cultivated his interests in botany, drawing, and music. He also applied himself to his military studies, something that would prove useful as the wars between France and other European countries continued under Napoleon, who became Emperor of the French in 1804.

Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, by George Dawe, circa 1823-25

Fighting against Napoleon

In 1805, Leopold made his first real appearance in the Russian army. He joined the headquarters of Grand Duke Constantine’s brother, Tsar Alexander I, in Moravia. Thus he was part of the Tsar’s retinue at the Battle of Austerlitz (December 2, 1805), in which Napoleon secured a major victory over Russia and Austria.

In 1806, Napoleon reorganized part of Austria’s territory into the French-controlled Confederation of the Rhine. This marked the demise of the Holy Roman Empire. The French occupied Coburg and then took Saalfeld. On December 9, 1806, Leopold’s father died. On December 15, Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld became part of the Confederation of the Rhine.

In 1807, Leopold again served with Russian forces against France. This time he was with Grand Duke Constantine. He distinguished himself at the battles of Guttstadt-Deppen, Heilsberg and Friedland. The last battle was a decisive French victory. Even though Leopold and other Coburgs had fought against him, Napoleon allowed Leopold’s eldest brother, Ernest, to take possession of the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld under the Treaty of Tilsit (July 7, 1807). In November, Ernest and Leopold went to Paris to thank Napoleon.

Leopold met Napoleon a second time at the Congress of Erfurt in October 1808, as part of Tsar Alexander’s suite. Leopold wanted to continue his military career with Russia, but Napoleon made clear that Ernest would lose his duchy if Leopold did so. Napoleon wanted Leopold to enter France’s service, but Leopold declined.

In 1813, after Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of and retreat from Russia, Leopold rejoined the Russian army, again under Grand Duke Constantine. He commanded a body of Russian cavalry in a series of engagements, including the battles of Lützen and Bautzen. His bravery at the battles of Kulm and Leipzig was rewarded with military decorations. In January 1814, Leopold and his cavalry entered France. They took part in the battles of Brienne, Arcis-sur-Aube, Le Fère Champenoise and Paris. Leopold witnessed the fall of Napoleon and the accession of King Louis XVIII to the French throne.

Marriage to Princess Charlotte of Wales

The Betrothal of Princess Charlotte and Prince Leopold, in the manner of George Clint, circa 1816

In June 1814, Leopold accompanied Tsar Alexander on a celebratory visit to England. While in London, the handsome 23-year-old general met 18-year-old Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales. She was the only legitimate child of King George III’s oldest son, George, Prince of Wales (known as the Prince Regent, later King George IV). Charlotte was engaged to Prince William of Orange, the son of King William I of the Netherlands, but she broke this off.

Leopold went back to the continent to attend the Congress of Vienna. When Napoleon escaped from Elba and returned to France in March of 1815, Leopold rejoined the Russian army. Russia did not participate in the Waterloo Campaign, but Leopold did spend time in Paris after Napoleon’s removal from the French throne. During this period, he and Charlotte corresponded privately. In late 1815, Charlotte informed her father that she favoured Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld as a candidate for her hand.

The Prince Regent invited Leopold to return to England. Doubts about the suitability of a poor, low-ranking German prince for the woman who was second-in-line to the British throne were soon dispelled. Leopold charmed the Prince Regent and those around him. Alicia Campbell, a governess of Princess Charlotte wrote:

I have heard nothing but good of [Prince Leopold]. I inquired of military men in London, who I could depend upon being open and candid with me, and the account was that he is a sensible and rather reserved man, and not dissipated as the generality of foreign princes are. (2)

Charlotte enthused:

No royal marriage I believe, ever promised to the individuals what this one does in point of domestic comfort, as without exaggeration I think I may say that [Prince Leopold] is a very charming and very superior person. (3)

Their engagement was formally announced in the House of Commons on March 14, 1816. Leopold was given British citizenship and the rank of general in the British army. Parliament granted the couple a stipend of £60,000 per year and purchased the estate of Claremont, southwest of London, as a residence for them. This was a huge step up for Leopold. His previous income was probably no more than £400 per annum. (4)

On the evening of May 2, 1816, Leopold and Charlotte were married in the crimson drawing room of Carlton House, the Prince Regent’s London home. Salvoes of artillery from St. James’s Park and the Tower of London announced the event to the city.

When Napoleon, in exile on St. Helena, learned of the match he said:

Prince Leopold was one of the handsomest and finest young men in Paris, at the time he was there. At a masquerade given by the Queen of Naples, Leopold made a conspicuous and elegant figure. The Princess Charlotte must doubtless be very contented and very fond of him. He was near being one of my aide-de-camps, to obtain which he had made interest and even applied; but by some means, very fortunately for himself, it did not succeed, as probably if he had, he would not have been chosen to be a future king of England. (5)

Leopold and Charlotte were happy together. The English painter Thomas Lawrence – commissioned by the Prince Regent to paint a portrait of Charlotte, who was then pregnant – spent time with the couple at Claremont in 1817. He reported:

It is exceedingly gratifying to see that [Princess Charlotte] both loves and respects Prince Leopold, whose conduct, indeed, and character, seem justly to deserve those feelings. From the report of the gentlemen of his household, he is considerate, benevolent, and just, and of very amiable manners. My own observation leads me to think that, in his behaviour to her, he is affectionate and attentive, rational and discreet; and, in the exercise of that judgment which is sometimes brought in opposition to some little thoughtlessness, he is so cheerful and slyly humorous that it is evident…that she is already more in dread of his opinion than of his displeasure.

Their mode of life is very regular: they breakfast together alone about eleven; at half-past twelve she came in to sit to me, accompanied by Prince Leopold, who stayed [a] great part of the time; about three, she would leave the painting-room to take her airing round the grounds in a low phaeton with her ponies, the Prince always walking by her side; at five, she would come in and sit to me till seven; at six, or before it, he would go out with his gun to shoot either hares or rabbits, and return about seven or half-past; soon after which, we went to dinner, the Prince and Princess appearing in the drawing-room just as it was served up. Soon after the dessert appeared, the Prince and Princess retired to the drawing-room, whence we soon heard the pianoforte accompanying their voices…..

After coffee, the card-table was brought, and they sat down to whist, the young couple being always partners, the others changing…. The Prince and Princess retire at eleven o’clock. (6)

Charlotte’s death

On November 3, 1817, Charlotte went into labour. Fifty hours later, on the evening of November 5, she delivered a 9-pound stillborn son. It was a breech birth, poorly managed by Charlotte’s doctor, who committed suicide three months later. Leopold told Thomas Lawrence:

She had been…for many hours, in great pain – she was in that situation where selfishness must act if it exists – when good people will be selfish, because pain makes them so – and my Charlotte was not…. She thought our child was alive; I knew it was not, and I could not support her mistake. I left the room for a short time: in my absence they took courage and informed her. When she recovered from it, she said, ‘Call in Prince Leopold – there is none can comfort him but me!’ …

My Charlotte thought herself very ill, but not in danger. And she was so well but an hour and a half after the delivery! And she said I should not leave her again – and I should sleep in that room…. (7)

On November 6, 1817, five and a half hours after her son’s delivery, Charlotte died of postpartum hemorrhage and shock. She was 21 years old. The governess Mrs. Campbell wrote on November 11, “Prince Leopold is calm, and exerts himself all in his power. He sees us all, and even tries to employ himself; but it is grief to look at him. He seems so heartbroken.” (8)

When Thomas Lawrence brought his finished portrait of Charlotte to Claremont, he met with Leopold.

The Prince was looking exceedingly pale; but he received me with calm firmness, and that low, subdued voice that you know to be the effort at composure. He spoke at once about the picture and of its value to him more than to all the world besides. From the beginning to the close of the interview, he was greatly affected. He checked his first burst of affection, by adverting to the public loss, and that of the royal family. ‘Two generations gone! – gone in a moment! I have felt for myself, but I have felt for the Prince Regent. My Charlotte is gone from this country – it has lost her. She was a good, she was an admirable woman. None could know my Charlotte as I did know her! It was my happiness, my duty to know her character, but it was my delight.’ (9)

Prince Leopold the widower

Prince Leopold, by Thomas Lawrence, 1821

Although he was no longer in line to become prince consort, Prince Leopold remained in England. He received an annuity of £50,000 per year and continued to be addressed as a Royal Highness. He moved into Marlborough House in London. The Crown had bought the residence for the royal couple in 1817, but Charlotte had died before the purchase was completed.

Leopold continued to miss Charlotte. On a visit to Coburg in 1819, he wrote to Alicia Campbell:

[T]he young and happy ménage of my brother [Ernest], as well as the sight of his fine child, gave me almost more pain than I had strength to endure. Time, which softens by degrees the most acute feelings, has kindly exercised its power on me; more accustomed to the sight of these objects I enjoy now somewhat more tranquility, but still I avoid as much as possible the sight of the poor little child. …