In describing Jean-Pierre Piat’s excursion through the streets of Paris in Napoleon in America, I tried to give an impression of what it was like to walk through the French capital in the early 1820s, during the reign of Louis XVIII. For a description of a stroll through Paris a decade later, it’s hard to beat the following extract from a 19th-century travel book. The anonymous British author provides a lively sense of a Sunday in Paris in the 1830s, during the reign of King Louis Philippe.

Vue de Boulevard Montmartre à Paris by Giuseppe Canella, 1830

More joyous on Sunday

“In Christendom, the manner in which the population, especially of a large city, spend the Sunday forms, perhaps, the best illustration of their education, habits, prejudices, slavery of opinion, subservience to priestcraft, and the influence of legislation.

“Sunday in London is unlike the same day in any town in Europe. The whole metropolis looks as if the plague had visited its population – melancholy seems to pervade all from east to west. It has an atmosphere of sadness, which seems despair to all who have been brought up or lived long on the Continent, and who are ignorant of our real virtues, as well as of the abominations and vice, which closed doors and window-shutters conceal.

“Paris, again, is more joyous on Sunday than on any other day in the week. Not that the people rest altogether from their usual productive labours, but that by devoting its early hours to industry and profit, and its afternoon and evening to gaiety, its animation is never suspended.

“On visiting that city soon after the last revolution, having been for several years accustomed to the solemn Sabbaths of England and North America, the first Sunday I spent in the capital of France was to me uncommonly striking. I was almost prepared, in the orthodox charity of a true Calvinist, to denounce the nation as having, in the course of eternal justice, drawn down upon it the retributive judgement of all just heaven. I was accompanied by an excellent, amiable and intelligent Canadian gentleman – of the old French school in his manners – a good Catholic, and liberal in politics and religion. Yet even he, from the force of habit, was shocked at seeing the Parisians at work, instead of being at mass.

“On our walking out early in the morning, we had not a little difficulty in crossing the streets, in consequence of the vast number of hackney coaches, and cabriolets, and nondescript vehicles, filled with parties going to enjoy the day in the country; and of numerous loaded wagons, some with hay, some with wine casks, others with medley loads. The shops, cafés, restaurants, were all open. We wended our way along the Rue Faubourg St. Honoré and turned into the church of the Assumption. Mass was performing; but the congregation consisted of only nine old women, three old men, seven little girls, and four boys, with three deformed beggars at the doors. When we left the church, rue St. Honoré was thronged.

A grand review

La Cité et le Pont Neuf, vus du quai du Louvre by Giuseppe Canella, 1832

“We met several detachments of national guards, horse and foot; also troops of the line, sappers and miners, horse artillery, and several baggage wagons. No church bells ringing, but the drums were beating in all quarters. As we turned down rue Castiglione, masons were at work on all the new buildings. We passed on to the Tuileries, where alterations were making in the palace and garden by the citizen king, and there also many were at work. At the same time a great movement of the populace across the Pont-Royal followed the crowd to the Champ de Mars.

“A grand review – 30,000 line, guards and artillery. The artillery exercise was considered sublime, and the fusillage brilliant. The king and staff, Duke of Orleans, Soult, &c. were present, and a vast multitude assembled. We crossed over the Pont de l’Ecole militaire. Hundreds of washerwomen and washermen were beating dirty linen to pieces in the huge floating sheds moored on the river – several people dragging nets for fish. We proceeded to the Champs-Elysées – people amusing themselves and their children in seeing the exhibitions of mountebanks, grimaciers, and polichenello, and on the swinging machines and wooden horses suspended – good exercise. Walked on to the Tuileries gardens – Parisians, in great numbers, sitting on chairs, under the shade of majestic trees; some conversing, some promenading, some playing with their children, and many reading newspapers, or sipping lemonade or coffee.

The Louvre and Notre Dame

Le marché aux fleurs, la Tour de l’Horloge, le Pont au Change et le Pont Neuf by Giuseppe Canella, 1832

“Spent two hours in the museum of the Louvre, where the bourgeois of Paris lounge each Sunday, admiring antique statues, and the old and new schools of painting, which my Canadian friend observed ‘is a better resort on the Sabbath than the London blue-ruin chapels.’ We crossed over the Seine to the quai Voltaire – walked to the Pont neuf – books exposed in great numbers for sale along the quays – shops all open – caricatures of Louis Philippe, grotesque, ridiculous, and political – portraits of Napoleon, the Duke of Reichstadt, and Napoleon’s exploits everywhere blazoned forth.

“Proceeded to the Cathedral Notre Dame. A circle congregated near the entrance, listening apparently with much delight, to a man and woman singing a romaunt (ballad); the man at the same time accompanying on a tambourine, and a boy playing on the violin. No service in the cathedral. On the opposite side stood a group round an Italian, playing on a barrel organ, and a woman singing a humorous ballad, in which naughty things were repeated of a priest and a woman in the Rue Montmartre. Passed on to the site of the archbishop’s palace, not one stone left over another – glorious privilege of a revolution, destruction without accountability. Came over the Pont neuf to the Palais-Royal, great crowds in the garden and in the Cabinets de lecture, reading newspapers, and talking politics. We read the journals. Dined at the Café de Chartres, waiters doubly active, it being Sunday. We left the restaurant, like all the world for a café, sipped a demi-tasse and petit-verre. Went to the Theatre Français.” (1)

You might also enjoy:

The Palais-Royal: Social Centre of 19th-Century Paris

New Year’s Day in Paris in the 1800s

Napoleon’s Funeral in Paris in 1840

Dangers of Walking in Vienna in the 1820s

Louis XVIII of France: Oyster Louis

The Tuileries Palace under Napoleon I and Louis XVIII

When the King of France Lived in England

Photos of 19th-Century French Royalty

- Austria and the Austrians, Vol. I (London, 1837), pp. 209-213.

What would Niagara Falls be like without all of its tourist trappings? To get an idea, we can look at the accounts of people who visited Niagara Falls before tourism became the area’s main industry. If Napoleon had made the journey to Niagara Falls in the early 19th century – as he does fictionally in Napoleon in America – this is what he would have found.

A General View of the Falls of Niagara by Alvan Fisher, 1820

This prodigious cascade

Niagara Falls consists of three waterfalls on the Niagara River, which flows north from Lake Erie into Lake Ontario. The river forms part of the border between Canada and the United States. The largest waterfall, Horseshoe Falls, is on the west side of the river and lies mainly in Canada. It is separated from the other falls by Goat Island, which is part of the United States. To the east of Goat Island is small Bridal Veil Falls (formerly known as Luna Falls), followed by tiny Luna Island, and then the large American Falls.

Niagara Falls was formed by the action of a continental ice sheet about 10,000 years ago. The rock beneath has been eroding ever since, changing the shape of the falls and causing them to retreat very slowly southward.

Although French explorers Jacques Cartier (1535) and Samuel de Champlain (1604) were told about Niagara Falls by the Native American inhabitants of the area, the first written eyewitness account of the falls comes to us from Belgian missionary Louis Hennepin, a member of Robert Sieur de la Salle’s expedition to North America. He saw the falls in December 1678.

We passed back by the great Fall of Niagara and employed ourselves during half a day in contemplating this prodigious cascade. …

[T]he discharge of so much water, coming from these fresh water seas, centres at this spot and thus plunges down more than six hundred feet, falling as into an abyss which we could not behold without a shudder. The two great sheets of water which are on the two sides of the sloping island that is in the middle, fall down without noise and without violence, and glide in this manner without din; but when this great mass of water reaches the bottom then there is a noise and a roaring greater than thunder.

Moreover this spray of the water is so great that it forms a kind of clouds above this abyss, and these are seen even at the time when the sun is shining brightly at midday. (1)

Early honeymooners to Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls from the American Side by John Vanderlyn, 1801-1803

In the early 19th century, Niagara Falls became a destination for well-off American and European visitors. In the spring of 1801, Theodosia Burr, daughter of US Vice-President Aaron Burr, and her husband Joseph Alston went on a “bridal tour” to Niagara Falls. In 1804, Napoleon’s brother Jérôme Bonaparte and his American bride Elizabeth (Betsy) Patterson followed suit.

The journal of Englishman John Grew, who visited Niagara Falls in July 1803, provides a sense of what the honeymooners might have encountered. He approached the falls from Fort Erie on the Canadian side.

At length we arrive at the tremulous precipice which has continually rolling over it the waters of the different lakes & rivers which run into them from the Lake of Woods to Lake Erie. We however do not stop at them but ride on to a house situated about a mile & a half farther down the river, which commands a fine view of the whole scene. Here we put up our horses, get some little refreshments & fit ourselves to descend the banks of the river that we may thoroughly view them. As we expected to be completely drenched by the sprays, we here undressed ourselves, & put on loose trousers, that we might have dry clothes upon our return.

We walk about a quarter of a mile towards the river where we came to a place where we were told by our conductor we should get down its bank, but its being so rocky so perpendicular & so high from the bed of the river that the prospect of it almost made us shudder. Determined however to make the attempt we followed our guide and by making use of our hands as well as feet – holding by rocks & trees & winding down by a kind of track that was made, we at length got down nearly half way. Here we came to a place for a number of feet entirely perpendicular where had been placed a kind of ladder for the convenience of those who wish’d to descend, but it was so broken & weak that without the assistance of our guide we could not have got down.

We however arrive at the bottom but have no sooner surmounted these difficulties than we found we had fresh ones to encounter. We had now to go nearly a mile over rocks along the bank and a rougher path cannot be conceived. We were heartily tired of our expedition before we had got half way, & wish’d ourselves safely lodged on the top of the bank. Not willing to turn back we proceeded over rocks & stones & sometimes on all fours to the foot of the Falls, & to have it in our power to say it, we just went under the edge of them – a situation which it is impossible to describe. The force of the air rushing from between the water & the rock is so great carrying the sprays with such violence that the only thing which in least resembles it is a summer storm or hurricane of wind & rain, but if possible the confined air – here – exceeds it in velocity. We make the best of our way from this shower bath, & scramble over the stones for a quarter of a mile where we ascended the bank by what is called the New Ladder. Compared with our descent we got up this path easily and for fifty or sixty feet had only to climb up a proper & strong ladder. We hastened back to the house where we had left our horses & clothes, & after resting ourselves we proceed on our way towards Chippewa.

When we get up to the Falls we again dismount to view them from the bank upon a line with them, & take our station from Table Rock, so called from its projecting over the river nearly 50 feet, & from its thinness being composed of only one solid sheet of rock. Here we had the best prospect of them. The noise however was so great (as well as below) that we could not hear one another speak. The view here is truly grand & majestic. The height from the bed of river is almost terrific. The sprays ascending in a column & forming vast clouds in the atmosphere is not the least surprising object, to which may be added the various tints & hues of them which the sun rendered dazzling & beautiful. We had now a full view of the rainbow which was nearly a complete circle and whose arch extended from one end of the fall to the other. …

An immense number of logs are continually falling down with the stream & the force with which they are carried is so great that the bark is entirely stripped off, and they carry the appearance of being turn’d, their ends likewise undergo various & great alterations. The timber which floats down and thrown amongst the rocks is sufficient to supply the surrounding country & towns of Chippewa & Niagara with fuel. (2)

A fashionable route

View of Niagara Falls by John Vanderlyn, 1801-1803

During the War of 1812, several battles were fought in the vicinity of Niagara Falls. This added to the popularity of the area after the war. A newspaper noted in 1816 that “the crowd of visitors this season from every part of the country has been unexampled.” (3)

In 1817, Augustus Porter, the owner of land and water rights on the American side of Niagara Falls, built a bridge to Goat Island. Prior to this, the only way to get to the island was to put a boat into the river a mile or so above the falls and then steer carefully between the rapids to avoid being swept over the precipice. Unfortunately the bridge was carried away by an unusual buildup of ice in the spring of 1818. Undaunted, Porter soon had a new bridge erected in a more favourable location. In addition, a flight of stairs was constructed on the American side so that ladies could safely descend to the bottom of the falls. These improvements were well-timed.

[Niagara Falls] has, during the present season, from the unusual number of visitors, been frequently spoken of in the public journals, and the journey to it is now considered a fashionable route. It is, however, one of those stupendous phenomena which repays the fatigue and gratifies the curiosity of all. It realizes expectation, though raised to an inordinate degree, and the contemplation of it has this salutary effect: to impress every one with an idea of his own insignificance. (4)

Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte, who fled to the United States after Napoleon’s 1815 defeat, visited Niagara Falls during this period.

No longer one of nature’s secret mysteries

Distant View of Niagara Falls by Thomas Cole, 1830

British author Frances Wright approached Niagara Falls from Lewiston on the American side in September 1819.

This mighty cataract is no longer one of nature’s secret mysteries; thousands now make their pilgrimage to it…over a broad highway; none of the smoothest, it is true, but quite bereft of all difficulty or danger. This in time may somewhat lessen the awe with which this scene of grandeur is approached….

[W]e alighted to look down from a broad platform of rock, on the edge of the precipice, at a fine bend of the river. From hence the blue expanse of [Lake] Ontario bounded a third of the horizon; Fort Niagara on the American shore; Fort George on the Canadian, guarding the mouth of the river, where it opens into the lake; the banks, rising as they approached us, finely wooded, and winding, now hiding and now revealing the majestic waters of the channel. Never shall I forget the moment when…I first beheld the deep, slow, solemn tide, clear as crystal, and green as the ocean, sweeping through its channel of rock with a sullen dignity of motion and sound, far beyond all that I had heard, or could ever have conceived. You saw and felt immediately that it was no river you beheld, but an imprisoned sea; for such indeed are the lakes of these regions. …

A mile farther, we caught a first and partial glimpse of the cataract, on which the opposing sun flashed for a moment, as on a silvery screen that hung suspended in the sky. It disappeared again behind the forest, all save the white cloud that rose far up into the air, and marked the spot from whence the thunder came. We now pressed forward with increasing impatience, and after a few miles reaching a small inn, we left our rude equipage, and hastened in the direction that was pointed to us.

Two foot-bridges have latterly been thrown, by daring and dexterous hands, from island to island, across the American side of the channel, some hundred feet above the brink of the fall; gaining in this manner the great island which divides the cataract into two unequal parts, we made its circuit at our leisure. From its lower point, we obtained partial and imperfect views of the falling river; from the higher, we commanded a fine prospect of the upper channel. Nothing here denotes the dreadful commotion so soon about to take place; the thunder, indeed, is behind you, and the rapids are rolling and dashing on either hand; but before, the vast river comes sweeping down its broad and smooth waters between banks low and gentle as those of the Thames. Returning, we again stood long on the bridges, gazing on the rapids that rolled above and beneath us; the waters of the deepest sea-green, crested with silver, shooting under our feet with the velocity of lightning, till, reaching the brink, the vast waves seemed to pause, as if gathering their strength for the tremendous plunge. …

Descending the ladder (now easy steps), and approaching to the foot of this lesser [American] Falls, we were driven away blinded, breathless, and smarting, the wind being high and blowing right against us. A young gentleman, who incautiously ventured a few steps farther, was thrown upon his back, and I had some apprehension, from the nature of the ground upon which he fell, was seriously hurt; he escaped, however, from the blast, upon hands and knees, with a few slight bruises. Turning a corner of the rock (where, descending less precipitously, it is wooded to the bottom) to recover our breath, and wring the water from our hair and clothes, we saw, on lifting our eyes, a corner of the summit of this graceful division of the cataract hanging above the projecting mass of trees, as it were in mid air, like the snowy top of a mountain. Above, the dazzling white of the shivered water was thrown into contrast with the deep blue of the unspotted heavens….

The wind at length having somewhat abated, and the ferryman being willing to attempt the passage, we here crossed in a little boat to the Canada side. The nervous arm of a single rower stemmed this heavy current, just below the basin of the Falls, and yet in the whirl occasioned by them….

Being landed two-thirds of a mile below the cataract, a scramble, at first very intricate, through, and over, and under huge masses of rock, which occasionally seemed to deny all passage, and among which our guide often disappeared from our wandering eyes, placed us at the foot of the ladder by which the traveller descends on the Canada side. From hence a rough walk along a shelving ledge of loose stones brought us to the cavern formed by the projection of the ledge over which the water rolls, and which is known by the name of the Table Rock.

The gloom of this vast cavern, the whirlwind that ever plays in it, the deafening roar, the vast abyss of convulsed waters beneath you, the falling columns that hang over your head, all strike, not upon the ears and eyes only, but upon the heart. For the first few moments the sublime is wrought to the terrible. This position, indisputably the finest, is no longer one of safety. A part of the Table Rock fell last year, and in that still remaining, the eye traces an alarming fissure, from the very summit of the projecting ledge over which the water rolls….

The cavern formed by the projection of this rock extends some feet behind the water, and could you breathe, to stand behind the edge of the sheet were perfectly easy. I have seen those who have told me they have done so; for myself, when I descended within a few paces of this dark recess, I was obliged to hurry back some yards to draw breath. …

From this spot (beneath the Table Rock), you feel, more than from any other, the height of the cataract and the weight of its waters. It seems a tumbling ocean; and you yourself what a helpless atom amid these vast and eternal workings of gigantic nature! …

Never surely did nature throw together so fantastically so much beauty with such terrific grandeur. Nor let me pass without notice the lovely rainbow that, at this moment, hung over the opposing division of the cataract as parted by the island, embracing the whole breadth in its span. …. We now ascended the precipice on the Canada side, and having taken a long gaze from the Table Rock, sought dry clothes and refreshment at a neighbouring inn. (5)

Infinitely exceeded anticipations

Niagara Falls by Karl Bodmer, 1839

In 1821 there were further enhancements for tourists at Niagara Falls.

[T]he accommodations for visitors are daily increasing here, and there are now besides Forsyth’s tavern on the Canadian side, two new houses of entertainment, Whitney’s on the American side, and Brown’s on the Canadian side of the river…. Scarce anything has yet been done to facilitate the access to the falls. You will be pleased to learn however, that this defect is likely to be soon remedied. During the late visit of our fellow-citizen Colonel Parkins to the falls, a subscription was set on foot by him and headed with the liberal sum of fifty dollars, for the purpose of laying a plank walk over the wet grounds, which must be passed in approaching the Falls, and of building a covered staircase to descend from Table Rock [on the Canadian side] immediately to the foot of the main sheet. The subscription rose in two days to near 200 dollars and the work is already in progress. (6)

British naval officer Basil Hall visited Niagara Falls in June 1827. He approached from Lockport on the American side.

[T]he Falls of Niagara…infinitely exceeded our anticipations. I think it right to begin with this explicit statement, because I do not remember in any instance in America, or in England, when this subject was broached, that the first question has not been, ‘Did the Falls answer your expectations?’

The best answer on this subject I remember to have heard of, was made by a gentleman who had just been at Niagara, and on his return was appealed to by a party he met on the way going to the Falls, who naturally asked him if he thought they would be disappointed. ‘Why, no,’ said he; ‘not unless you expect to witness the sea coming down from the moon!’ …

The first glimpse we got of the great Fall, was at the distance of about three miles below it, from the right or eastern bank of the river. Without attempting to describe it, I must say that I felt at the moment quite sure no subsequent examination, whether near or remote, could ever remove, or even materially weaken, the impression left by this first view.

From the time we discovered the stream, and especially after coming within hearing of the cataract, our expectations were of course wound up to the highest pitch. Most people, I suppose, in the course of their lives, must, on some occasion or other, have found themselves on the eve of a momentous occurrence; and by recalling what they experienced at that time, will perhaps understand better what was felt, than I can venture to describe it. I remember myself experiencing something akin to it at St. Helena, when waiting in Napoleon’s outer room, under the consciousness that the tread which I heard was from the foot of the man who, a short while before, had roved at will over so great a portion of the world; but whose range was now confined to a few chambers – and that I was separated from this astonishing person, only by a door, which was about to open. So it was with Niagara. I knew that at the next turn of the road, I should behold the most splendid sight on earth, — the outlet to those mighty reservoirs, which contain, it is said, one-half of the fresh water on the surface of our planet. …

The scenery in the neighbourhood of Niagara has, in itself, little or no interest, and has been rendered still less attractive by the erection of hotels, paper manufactories, saw-mills, and numerous other raw, staring, wooden edifices.…

I had the satisfaction of walking over the whole of Goat Island one day with the proprietor, who seemed unaffectedly desirous of rendering it an agreeable place of resort to strangers. He had been recommended, he told me, by many people, to trim and dress it; to clear away most of the woods; and by all means to extirpate every one of the crooked trees. I expressed my indignation at such a barbarous set of proposals, and tried hard to explain how repugnant they were to all our notions of taste in Europe. His ideas, I was glad to see, appeared to coincide with mine; so that this conversation may have contributed, in some degree, to the salvation of the most interesting spot in all America. (7)

Hall went into the cavern beneath Horseshoe Falls, which had so frightened Frances Wright.

We reached a spot 153 feet from the outside, or entrance, by the assistance of a guide, who makes a handsome livelihood by this amphibious pilotage. There was a tolerably good, green sort of light within this singular cavern; but the wind blew us first in one direction then in another with such alarming violence, that I thought at first we should be fairly carried off our feet, and jerked into the roaring caldron beneath. This tempest, however, was not nearly so great an inconvenience as the unceasing deluges of water driven against us. Fortunately the direction of this gale of wind was always more or less upwards, from the pool below, right against the face of the cliffs; were it otherwise, I fancy it would be impossible to go behind the Falls, with any chance of coming out again. Even now there is a great appearance of hazard in the expedition, though experience shows that there is no real danger. Indeed the guide, to reassure us, and to prove the difficulty of the descent, actually leaped downwards, to the distance of five or six yards, from the top of the bank of rubbish at the base of the cliff, along which the path is formed. The gusts of wind rising out of the basin or pool below, blew so violently against him that he easily regained the walk. …

All parties agreed that there was considerable difficulty in breathing; but while some ascribed this to a want of air, others asserted that it arose from the quantity being too great. The truth, however, obviously is, that we have too much water; not too much air. For I may ask, with what comfort could any man breathe with half a dozen fire-engines playing full in his face? …

Though I was only half an hour behind the Fall, I came out much exhausted, partly with the bodily exertion of maintaining a secure footing while exposed to such buffeting and drenching, and partly, I should suppose, from the interest belonging to this scene, which certainly exceeds any thing I ever witnessed before. All parts of Niagara, indeed, are on a scale which baffles every attempt of the imagination to paint, and it were ridiculous, therefore, to think of describing it. The ordinary materials of description, I mean analogy, and direct comparison with things which are more accessible, fail entirely in the case of that amazing cataract, which is altogether unique. (8)

You might also enjoy:

Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte, Napoleon’s American Sister-in-Law

Joseph Bonaparte: From King of Spain to New Jersey

Taking the Waters at Saratoga Springs and Ballston Spa

A Skeleton City: Washington DC in the 1820s

Advice on Settling in New York in 1820

A Summer Night in New York City in the 1800s

Post-houses and Stage-houses in the Early 1800s

Some 19th-Century Packing Tips

- John Gilmary Shea, A Description of Louisiana by Father Louis Hennepin (New York, 1880), p. 378.

- John Grew, Journal of a Tour from Boston to Niagara Falls and Quebec (1803), pp. 69-73.

- “Falls of Niagara,” The Supporter (Chillicothe, Ohio), December 3, 1816.

- “Niagara Falls (From the American Daily Advertiser),” The Morning Post (London, England), October 26, 1818.

- Frances Wright, Views of Society and Manners in America (London, 1821), pp. 237-245.

- “Falls of Niagara [From the Boston Daily Advertiser],” The Morning Post (London, England), October 2, 1821.

- Basil Hall, Travels in North America in the Years 1827 and 1828, I (Edinburgh, 1829), pp. 177, 180-181, 190, 192.

- Ibid., pp. 198-199, 204.

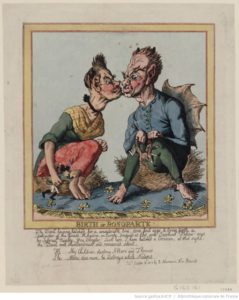

John Bull and Bonaparte, one of many songs about Napoleon written during the Napoleonic Wars. Source: Broadside Ballads Online from the Bodleian Libraries http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/

More songs have been written about Napoleon Bonaparte than about any other military leader in history. Hundreds of songs about Napoleon were written and performed in the 19th century. Napoleon also features as the subject matter of some 20th- and 21st-century songs. If songs that simply mention Napoleon are added to the tally, the number probably reaches into the thousands. Here’s a look at popular songs about Napoleon that have been written in English.

Napoleon in Popular Song

The Napoleonic Wars had an enormous influence on cultural life in Great Britain. According to Scottish folk song collector Gavin Greig, “the twenty years that ended with Waterloo have left more traces on our popular minstrelsy than any other period of our history has done.” (1) Popular song was “the most widespread and influential form of literary and musical expression” in Britain at the time, and Napoleon was a common subject matter.

Never were so many melodies, verses and choruses expended in praise, condemnation, pity and ridicule as in the case of Napoleon. (2)

Many songs about Napoleon were printed cheaply as texts on broadside ballad sheets.

Sold in large numbers on street-corners, in town-squares and at fairs by travelling ballad-singers and pinned on the walls of alehouses and other public places, [broadside ballads] were sung, read and viewed with pleasure by a wide audience, but have been handed down to us in only small numbers. (3)

Ballad singers sang on the streets or in pubs in exchange for pennies. Performances were often a cappella, with lyrics and tunes varying from one appearance to another.

As in British caricatures of the time, Napoleon was often portrayed in an unflattering manner: “little Boney,” “the Corsican monster,” “the Corsican pest,” etc. During 1803-1805, when Napoleon was threatening to invade Britain, songs formed part of a propaganda campaign aimed at arousing British patriotism and getting more men to enlist in the army and the navy.

In later songs, particularly those written after Napoleon’s 1815 defeat and exile to St. Helena, Napoleon is regarded more favourably: “that hero bold,” “brave Napoleon,” “Bonaparte, the Frenchman’s pride.” These songs tend to focus on Napoleon as a man, rather than as an enemy leader.

[B]y envisaging a noble husband permanently separated from his family, people could articulate and indeed ennoble their own grief for lost servicemen, or – more happily – valorise the less permanent sacrifices and hardships endured whilst husbands or lovers served on foreign stations. In these songs, Napoleon is always the individual, his opponents the state apparatus, this in itself securing him sympathy among much of the populace. (4)

Some songs about Napoleon became truly popular and were passed down through the generations. These were written down by folk song collectors in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Henry Burstow, a Sussex shoemaker and bell ringer who was born in 1826 and died in 1916, claimed he knew 420 songs, at least seven of which were about Napoleon (Boney’s Farewell to Paris, Boney in St. Helena, Boney’s Lamentation, Bonny Bunch of Roses, Deeds of Napoleon, Dream of Napoleon, The Grand Conversation of Napoleon).

Songs about Napoleon, 1803-1821

Here is a selection of songs about Napoleon written during his lifetime, with a sample of the lyrics. For the full text, click on the song title, which will take you to the relevant broadside sheet in Broadside Ballads Online from the Bodleian Libraries. To listen to the songs, go to Soundcloud, where Oskar Cox Jensen, the author of Napoleon and British Song, 1797-1822 (2015), has posted recordings of several of the songs listed below, as well as other songs about Napoleon. You can also listen to the first verses of several Napoleonic ballads, and many other broadside ballads, by following the “Free First Verse Recordings” link on traditional folksinger Dick Holdstock’s website. Dick is the author of the excellent Again With One Voice, British Songs of Political Reform, 1768 to 1868 (2021).

John Bull and Bonaparte (1803)

Tune – “Blue Bell of Scotland”

When and O when does this little Boney come?

Perhaps he’ll come in August! Perhaps he’ll stay at home;

But it’s O in my heart, how I’ll hide him should he come.

That is “hide” in the sense of hitting with a stick.

High on a rock, his cunning eye

Surveys half Europe at a glance,

Fat Holland, fertile Italy,

Old Spain, and gay regen’rate France.

Little Boney A-cockhorse (1803)

O dear, Little Boney’s coming over;

With his legions of troops to land them at Dover:

But our brave Volunteers they’ll soon do him over,

And blow him quite over to France!

The Pitman’s Revenge Against Buonaparte

Aye, Bonaparte’s sel aw’d tyek,

And thraw him i’ the burning heap,

And wi’ greet speed aw’d roast him deed;

His marrows, then, aw wad nae heed. (5)

A Dumpling for Buonaparte (1805)

The now crop-sick hero must soon change his note

For a large Norfolk dumpling sticks fast in his throat,

Then let us rejoice that we live in a land

Where GEORGE has some thousands such-like at command.

Crocodile’s Tears: Or, Bonaparte’s Lamentation. A New Song (1805 or later)

Tune – “Bow, wow, wow.”

By gar, I find my ardor fail, and all my courage cool, Sir,

De World confess I am de Knave – de English call me fool, Sir:

Hard fate! Alas, that I am both! My heart of grief is full, Sir.

By gar, me wish I was at peace! With honest Johnny Bull! Sir.

Tune – “Despairing beside a clear Stream”

Ah! Boney, thy wishes are vain,

Thy murd’ring schemes lay aside;

For Britains are lords of the Main,

And Providence fights on their side.

The Threatening of the Whole Continent Against Buonaparte (after 1810)

Swaggering Boney,

Galloping Boney,

Runaway Boney,

Where are you now?

Bonaparte’s Mistake at Germany (1813)

They set fire to his tail so off Boney runs,

O poor Boney, long-headed Boney,

Short-legged Boney we’ll soon have you now.

The Devil’s Own Darling (1814)

His race is run at last, tho’ for a long time past,

He never studied anything but evil, O.

Although he was but small he’d swagger over all.

Led on by his dear friend, old nick the Devil, O.

Boney’s Lamentation (1814)

There are different versions of this song about Napoleon’s exile to Elba, one in the Broadside Ballads Online collection, and this one, sung in 1893 by Henry Burstow (who learned it from his father) for folk song collector Lucy Broadwood. She identified the tune as a variant of “the Princess Royal,” which was in print in English books as early as 1727. (6)

I did pursue the Egyptians sore,

Till Turks and Arabs lay in gore;

The rights of France I did restore

So long in confiscation.

I chased my foes through mud and mire

Till in despair my men did tire.

Then Moscow town was set on fire.

You can listen to Irish traditional singer Jim MacFarland performing a version of “Boney’s Lamentation” on the Irish Traditional Music Archive.

Who was it spread war’s dire alarms,

And set all Europe up in arms?

Who shower’d upon us discord’s storms?

This song, about Napoleon’s escape from Elba and return to France, is also known as “Boney’s Return to Paris.”

Tune – “London now is out of Town”

London now is come to town

Few are found who tarries,

Boney there, has made them stare,

And drove them back from Paris.

Boney’s Total Defeat, and Wellington Triumphant (1815)

You’ve heard of a battle that’s lately been won,

By our brave British troops under Duke Wellington,

How they bang’d the French army and made Boney run,

Before the brave lads of Old England,

Huzza for Old England’s brave boys.

Napoleon’s Farewell to Paris (1815)

My name’s Napoleon Bonaparte, the conqueror of nations

I’ve banished German legions, and drove Kings from their thrones,

I’ve trampled Dukes and Earls, and splendid congregations,

Tho’ they’ve now transported me to St. Helena’s shore.

Napoleon Buonaparte’s Exile to St. Helena (1815)

In Rochford dock the fleet lay moored,

The streamers wavered in the wind,

When Napoleon Buonaparte came on board.

Saying, ‘where shall I some refuge find.’

Songs about Napoleon, 1821-1899

Napoleon died on May 5, 1821, as a prisoner on the remote British island of St. Helena. The following songs were written after his death.

Napoleon on the Isle of St. Helena (1821)

The Parliament of England and your Holy Alliance,

To a prisoner of war you may now bid defiance,

For your base intrigues and your base misdemeanors,

Have cause him to die on the Isle of St. Helena.

Boney was a Warrior (after 1821)

An Anglo-French sea shanty.

Oh, Boney marched to Moscow, way, hay, yah!

Across the Alps through ice an’ snow, Jean François!

Shantyman (solo): Boney was a warrior,

All (refrain): Way-ay-ya,

Shantyman (solo): A warrior, a terrier,

All (refrain): John François!

The Bonny Bunch of Roses (before 1832)

The song takes the form of a conversation between Napoleon’s son (Napoleon II) and his mother, Napoleon’s second wife Marie Louise. It says Napoleon was defeated because he failed to beware of the “bonny bunch of roses”: the British army and, symbolically, the union of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales.

But while our bones do moulder,

And weeping willows round us grow,

The deeds of bold Napoleon

Will sting the bonny bunch of Roses, O.

The Deeds of Napoleon (after 1832)

Tune – “Mouth of the Nile”

Tho’ Kings he did dethrone and some thousands caused to groan,

Yet we miss the long lost emperor Napoleon.…

Oh! Bring him back again it will ease the Frenchman’s pain,

And in a tomb of marble we will lay him with his son.

The Grand Conversation on Napoleon (between 1832 & 1840)

Ah England! He cried, did you persecute that hero bold,

Much better had you slain him on the plains of Waterloo;

Napoleon he was a friend to heroes all, both young and old,

He caus’d the money for to fly wherever he did go.

You can listen to folk singer Andy Turner singing a version of “The Grand Conversation of Napoleon” on A Folk Song A Week.

Napoleon’s Dream (before 1838)

When I led them to honour and glory,

On the plains of Marengo, I tyranny hurled,

And wherever my banner, the Eagle, unfurled,

Twas the standard of freedom all over the world,

The signal of fame! Cried Napoleon.

Removal of Napoleon Buonaparte’s Ashes (1840)

This song refers to the return of Napoleon’s remains to France in 1840.

But of a valiant Corsican, as ever stood on Europe’s land,

I am inclined to sing in praise, how noble was his heart,

In every battle manfully, he struggled hard for liberty.

And to the world a terror was, Napoleon Bonaparte.

Napoleon the Brave (before 1855)

Napoleon is no more, the French did him adore,

Their allied powers did join their kingdom for to save,

They ne’er could him subdue, till he made some of them rue

And they were in a stew, by Napoleon the Brave.

Bonaparte Crossing the Rhine

This tune, also known under other “Napoleon Crossing…” titles, may actually have originated as a military march during the Napoleonic Wars (see the Banjo Hangout Discussion Forum).

Bonaparte’s Retreat

This song, which nearly causes a brawl between General Charles Lallemand and a fiddler in Napoleon in America, originated as a fiddle tune in the 19th century.

Songs about Napoleon, 1900-present

Old Napoleon, Hank Thompson (1957)

Waterloo, Stonewall Jackson (1959)

Done with Bonaparte, Mark Knopfler (1996)

The Ballad of Sir Hudson Lowe, Roger D’Arcy (2017)

Hudson Lowe was the governor of St. Helena during Napoleon’s imprisonment on the island.

You might also enjoy:

What was Napoleon’s favourite music?

Napoleon’s Castrato: Girolamo Crescentini

Giuseppinia Grassini, Mistress of Napoleon & Wellington

Caricatures of Napoleon on Elba

Caricatures of Napoleon on St. Helena

Boney the Bogeyman: How Napoleon Scared Children

Supporters of Napoleon in England

- Vic Gammon, “The Grand Conversation: Napoleon and British Popular Balladry,” http://www.mustrad.org.uk/articles/boney.htm. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Oskar Cox Jensen, Napoleon and British Song, 1797-1822 (London, 2015), p. 1.

- “About The Project,” Broadside Ballads Online from the Bodleian Libraries, http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/about. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Napoleon and British Song, 1797-1822, p. 133.

- The Tyne Songster, A Choice Selection of Songs in the Newcastle Dialect (Newcastle, 1840), pp. 33-34.

- Lucy E. Broadwood, English Traditional Songs and Carols (London, 1908), pp. 34-35, 117.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, had a morganatic marriage

A morganatic marriage is a marriage contracted between a member of a royal or noble family and someone (typically, but not necessarily) of lower status, in which the spouse and any resulting children have no claim to royal or noble rank, title, or hereditary property. Another term for a morganatic marriage is a left-handed marriage, stemming from the custom of the groom extending his left hand, rather than his right hand, to the bride. Morganatic marriages primarily took place in the Germanic areas of the Holy Roman Empire and its successors between the 15th and 19th centuries.

A way to limit the claims of sons

Morganatic marriage originated in the law of the Lombards, a Germanic people who ruled much of Italy from 568 until they were conquered by Charlemagne in 774. Feudal German society was divided into legally defined classes: upper nobility; lower nobility; burgher; peasant. Each class had specific rights and obligations, and people were expected to marry within their class. A morganatic union enabled royals and nobles to marry someone of lower status.

Morganatic comes from the German word “Morgengabe” which means “morning gift.” It refers to the dowry given by the husband to the wife on the morning after the wedding. The idea was that the wife’s and the children’s share of the husband’s estate was limited to this dowry.

By the 15th century, morganatic marriage had become a legal tool in many of the autonomous German territories of the Holy Roman Empire. Since feudal law required land to be divided equally among male siblings, morganatic marriage offered a method by which noble families could reduce the fragmentation of their estates, by confining inheritance to one or a few sons. Even if younger sons married someone of the same class, the claims of their offspring could be limited. Second marriages, where there were already heirs from a first marriage, were also commonly morganatic marriages, for the same reason. A morganatic marriage was also a way to sanctify a relationship with a mistress.

Marriages of love

Morganatic marriages tended to be love matches, as indicated in these observations by a British visitor to Austria in the 1830s.

I first heard, without well comprehending the meaning, the term ‘Left-handed marriages’…at Munich, where some members of the royal family have had the philosophical courage, at the expense of princely dignity, to marry those they loved and with whom they knew they could be happy, rather than ally themselves politically with those with whom they might probably have no community of feelings, affections, or ideas. But these marriages, virtuous and Christian in celebration as they are, do not figure on the leaves of the Gothaischer- genealogischer – Hof-Kalender, or on those of other courtly or gothic registers. …

Removed by choice for a great part of the year from the capital, Archduke John, of Austria, resides upon his lands in Styria. There he lives in happy simplicity, with an amiable wife, by a left-handed marriage. This marriage was grounded on reason and affection. He considered that if he married a royal princess, his offspring would be included with the already too multiplied number, who, with their probable descendants, must live out of the civil list allowance of the empire; he, in consequence, wisely determined on marrying a woman formed to be loved, and fitted to be his friend and companion, as well as a proper mother for his offspring. For the benefit of the latter, whom he is determined not to leave as heritages to be provided for by the country, he is turning his lands and mines to the best account that can be effected by well applied skill. (1)

By the 20th century, morganatic marriages had become increasingly rare. One of the most famous was that of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, to Sophie Chotek, Duchess of Hohenberg, on July 1, 1900. They were both assassinated at Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, thus triggering World War I.

In 1936, King Edward VIII proposed that he be allowed a morganatic marriage to Wallis Simpson, as a way of getting around the fact that a British king could not marry a divorcée. But morganatic marriages are not part of British law, and this option was rejected by the British cabinet. The King abdicated to proceed with his love match.

Napoleon and morganatic marriage

Morganatic marriage did not exist in French law. However, historically in the French royal family there were “secret marriages” that were similar to morganatic marriages. These were authorized by the king, but not officially acknowledged; they took place in private, and the wife did not assume her husband’s rank, title, or coat of arms. An example is the marriage of Louis XIV to Françoise d’Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon, in 1683 or 1684.

Napoleon took a commanding interest in marriages within the Bonaparte family, wanting to be able to select, or at least approve, spouses for his siblings, especially his brothers. When he became Emperor of the French in 1804, Napoleon specified in the imperial constitution that princes of the imperial family could not marry without the Emperor’s authorization. Should an unauthorized marriage take place, both the offender and his descendants would be deprived of their rights of inheritance. A decree of March 30, 1806, further stated that unauthorized marriages would be considered null and void, and that any children of such marriages would be deemed illegitimate.

Napoleon tried to convince his brother Lucien to give up his wife, Alexandrine de Bleschamp, the widow of a French banker. Lucien refused. He and his children were barred from the imperial line of succession. Napoleon had more success with his youngest brother Jérôme, who quickly renounced his first wife, the American Elizabeth Patterson, upon being threatened with the removal of imperial privileges.

Napoleon married Jérôme off to a German princess, Catharina of Württemberg, who died in 1835. In 1840, Jérôme contracted a morganatic marriage with a rich Italian widow named Justine (Giustina) Bartolini-Baldelli. This ensured that Jérôme’s title and privileges as Prince of Montfort – granted by Catharina’s father – and his claims as a Bonaparte would not extend to Giustina or any children (they never had any).

Another notable morganatic marriage connected with Napoleon was that of his widow Marie Louise, an Austrian Habsburg princess who was then Duchess of Parma, to Austrian nobleman Count Adam Albert von Neipperg, who appears in Napoleon in America. They wed on September 7, 1821, four months after Napoleon’s death. At the time, Marie Louise already had three children with Neipperg. Neipperg did not become Duke of Parma, and the children were not given Habsburg estates. On February 17, 1834, four years after Neipperg’s death, Marie Louise married French Count Charles René de Bombelles, in another morganatic marriage.

You might also enjoy:

Lucien Bonaparte, Napoleon’s Scandalous Brother

Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte, Napoleon’s American Sister-in-Law

Adam Albert von Neipperg, Lover of Napoleon’s Wife

The Marriage of Napoleon and Marie Louise

What did Napoleon’s wives think of each other?

10 Interesting Facts About Napoleon’s Family

Fanny Fern on Marriage in the 19th Century

Photos of 19th-Century French Royalty

- Austria and the Austrians, Vol. I (London, 1837), pp. 247, 250-51.

Giuseppina Grassini in the role of Zaira, by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, circa 1805

Giuseppina Grassini was a famous Italian opera singer of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Though her voice was a contralto, she worked it into a higher register to sing roles written for mezzo-sopranos. Napoleon Bonaparte was enraptured by the quality of Madame Grassini’s singing, as well as by her physical beauty. He took her as his lover and paid her to sing at his court for many years. Giuseppina Grassini also became the lover of Napoleon’s nemesis, the Duke of Wellington.

Humble origins

Maria Camilla Giuseppina Grassini (or Josephina, as she later signed herself) was born at Varese, north of Milan, on April 18, 1773. Her parents were Antonio Grassini, a bookkeeper for a local convent, and Isabella Luini, who claimed descent from the painter Bernardino Luini, a student of Leonardo da Vinci. Antonio and Isabella had 18 children. Young Giuseppina stood out for her beautiful voice. She sang like a nightingale to the accompaniment of her mother’s violin. (1)

Giuseppina Grassini’s first teacher was the church organist Domenico Zucchinetti. He recommended that she be sent to Milan to study for the opera. There Count Alberico Belgiojoso became her protector, promoter and lover. He oversaw Giuseppina’s musical education and arranged for her stage debut in Parma in 1789, at the age of 16. She sang small roles in two comic operas: Pietro Guglielmi’s La pastorella nobile and Domenico Cimarosa’s La ballerina amante. The following year, she sang at Milan’s La Scala in three more comic operas.

In 1792, Giuseppina began to appear in tragic operas. She performed in Vicenza, Venice, Milan, Naples and Ferrara, to growing acclaim. In 1796, she starred with one of her teachers, the castrato Girolamo Crescentini, in the premieres of two operas, performing roles for which she became famous: Giulietta in Giulietta e Romeo by Niccolò Zingarelli, and Horatia in Gli Orazi e i Curiazi by Cimarosa.

Madame Grassini meets Napoleon

Madame Grassini – La Grassini – was thus already a celebrated singer when French troops led by General Napoleon Bonaparte entered Milan triumphantly on May 15, 1796, after defeating Austrian troops at the Battle of Lodi. Count de Las Cases, to whom Napoleon dictated his memoirs when imprisoned on St. Helena, implied that Giuseppina Grassini tried to seduce the French general. He reported Grassini as telling Napoleon in 1800:

I was then [in 1796] in the full lustre of my beauty and my talent. My performance in the Virgins of the Sun [La vergine del sole, by Gaetano Andreozzi] was the topic of universal conversation. I fascinated every eye and inflamed every heart. The young General [Napoleon] alone was insensible to my charms, and yet he was the only object of my wishes! What caprice, what singularity! When I possessed some value, when all Italy was at my feet, and I heroically disdained its admiration for a single glance from you; I was unable to attain it, and now, how strange an alteration, you condescend to notice me – now, when I am not worth the trouble and am no longer worthy of you! (2)

However, Giuseppina Grassini’s biographer, Arthur Pougin, makes no mention of Napoleon seeing Grassini in 1796, or of Grassini appearing in La vergine del sole in that year. What is clear is that when Napoleon returned to Milan prior to the Battle of Marengo in 1800, he saw Madame Grassini perform at La Scala on June 4. Later that night, when Napoleon’s private secretary Bourrienne woke him to announce that Genoa had capitulated to French forces, “Madame Grassini also awoke.” (3) According to Bourrienne:

I several times took tea with her and Bonaparte in the General’s apartments…. Napoleon was charmed with Madame Grassini’s delicious voice, and if his imperious duties had permitted it he would have listened with ecstasy to her singing for hours together. (4)

Napoleon was so taken with Madame Grassini’s voice and person that he insisted on her joining him in Paris. On July 14, 1800, she sang at the national fête under the dome of the Invalides. Napoleon provided Madame Grassini with a house and an income.

Having a tolerably rich establishment of fifteen thousand francs a month, she exhibited her brilliancy at the theatre and the concerts at the Tuileries, where her voice performed wonders. But at the time [Napoleon] made a point of avoiding scandal; and not wishing to give Josephine [his wife], who was excessively jealous, any subject of complaint, his visits to the beautiful vocalist were abrupt and clandestine. Amours without attention and without charms were not likely to satisfy a proud and impassioned woman, who had something masculine in her character. [Madame Grassini] had recourse to the usual infallible antidote; she fell violently in love with the celebrated violin player, [Pierre] Rode. (5)

Accompanied by Rode, Grassini left Paris in November 1801, embarking on a concert tour of Holland and Germany.

Madame Grassini in London

In 1803, Giuseppina Grassini played for four months at the Haymarket Theatre in London. She also sang there in 1804.

This very handsome woman was in every thing the direct contrary of her rival [Elizabeth Billington]. With a beautiful form, and a grace peculiarly her own, she was an excellent actress, and her style of singing was exclusively the cantabile, which became heavy à la longue, and bordered a little on the monotonous: for her voice, which it was said had been a high soprano, was by some accident reduced to a low and confined contralto. She had entirely lost all its upper tones, and possessed little more than one octave of good natural notes; if she attempted to go higher, she produced only a shriek, quite unnatural, and almost painful to the ear.

Her first appearance was in La Vergine del Sole…well suited to her peculiar talents; but her success was not very decisive as a singer, though her acting and her beauty could not fail of exciting high admiration. So equivocal was her reception, that when her benefit was to take place she did not dare encounter it alone, but called in Mrs. Billington to her aid, and she, ever willing to oblige, readily consented to appear with her. The opera, composed for the occasion by [Peter] Winter, was Il Ratto di Proserpina, in which Mrs. Billington acted Ceres, and Grassini Prosperine. And now the tide of favour suddenly turned; the performance of the latter carried all the applause, and her graceful figure, her fine expression of face, together with the sweet manner in which she sung several easy simple airs, stamped her at once the reigning favourite…. Not only was she rapturously applauded in public, but she was taken up by the first society, fêtée, caressed, and introduced as a regular guest in most of the fashionable assemblies. Of her private claims to that distinction it is best to be silent, but her manners and exterior behaviour were proper and genteel. (6)

Madame Grassini continued to perform in London for the next two years. Thomas de Quincey found her voice “delightful…beyond all that I had ever heard.” (7)

Back in Paris

In 1807, Giuseppina Grassini returned to France, engaged to sing in Napoleon’s newly established imperial choir, along with her former teacher Girolami Crescentini. She received a salary of 36,000 francs, a pension of 15,000 francs, and the proceeds of an annual benefit concert, as well as other rewards.

One evening in 1810, she and Signor Crescentini performed together at the Tuileries, and sang in ‘Romeo and Juliet.’ At the admirable scene in the third act, the Emperor Napoleon applauded vociferously, and Talma, the great tragedian, who was among the audience, wept with emotion. After the performance was ended, the Emperor conferred the decoration of a high order on Crescentini, and sent Grassini a scrap of paper on which was written, ‘good for 20,000 livres – Napoleon.’ (8)

Madame Grassini became a well-known figure in Paris.

Received everywhere, loved by everyone, she had a natural kindliness, spontaneity, true and original. She spoke a mixed jargon of French and Italian, all her own, which allowed her to say anything, and by which she profited to make the most amusing remarks and the most amusing confidences, blaming what she said on her ignorance of the language whenever she said anything that could shock or hurt someone. (9)

Attentions of the Duke of Wellington

After Napoleon was exiled to Elba in 1814, Giuseppina Grassini attracted the favours of the Duke of Wellington, who was then serving as the British ambassador to France. On November 13, Henrietta Ponsonby, Countess of Bessborough, wrote to Granville Leveson Gower from Paris:

The Duke of Wellington is so civil to me, and I admire him so much as a hero that it inclines me to be partial to him, but I am afraid he is behaving very ill to that poor little woman [Wellington’s wife Kitty]: he found great fault for it, not on account of making her miserable or of the immorality of the fact, but the want of procédé and publicity of his attentions to Grassini. (10)

The affair continued after Napoleon’s return to France and his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. The composer Felice Blangini described a meeting with Wellington and Grassini in July of that year.

As I often saw Madame Grassini, she took me to Lord Wellington’s, where we often made music. Lord Castlereagh was a constant visitor there; he sang with us, very tolerably for an English minister. When Madame Grassini was at these small gatherings at Lord Wellington’s, she recited and sang scenes from Cleopatra and from Romeo e Giulietta. Alone in the centre of the salon, she gestured as if she were on the stage, and with the aid of a big shawl she dressed up in various ways. I do not remember whether, during these sessions, she sang the arias that end with a ‘sgauardo d’amor’; but what I am sure of is that Lord Wellington was overjoyed in ecstasy. (11)

Regarding soirées hosted by Wellington in Paris in 1816, the Countess de Boigne wrote:

I recall that on one occasion he decided to make Grassini, then in possession of his favours, the queen of the evening. He placed her on a raised sofa in the ballroom and never left her side. He had her served first before anyone else, arranged everyone so that she could dance, gave her his hand to take her into supper first, sat her next to him, and finally paid her the kind of attention normally granted only to princesses. (12)

Retirement

In 1817, Giuseppina Grassini returned to Italy. She continued to appear in operas, but her voice was not what it used to be, and she retired from the stage in 1823. She settled in Milan and devoted herself to teaching. Captain Gronow recollected:

When I first met her in 1825 she still possessed some remains of the remarkable beauty which had won for her the attention and admiration of so many of the great men of the age. Napoleon and Wellington, the Marshals of France, the Generals of the allied armies, English, Russians, Prussians, Austrians, as well as the Dukes and Marquises of the Restoration, had all bowed before Grassini’s shrine, and had all been received with the same Italian bonhomie and liberal kindness. She would often say, ‘Napoleon gave me this snuff-box; he placed it in my hands one morning when I had been to see him at the Tuileries, and added, ‘Voilà pour toi; tu es une brave fille!’ He was indeed a great man, but he would not follow my advice. Il aurait du s’entendre avec ce cher Vilainton. By the by, c’est ce brave Duc qui m’a donné cette broche….’ And so she would run on, with anecdotes and remarks on a long list of admirers.

All Madame Grassini’s recollections came out quite naturally, with true southern frankness, or rather cynicism; and she narrated her liaisons in as unconcerned a manner before every one she met, as she were speaking of her drive in the Bois de Boulogne. Her face must have been in her youth still handsomer than that of her niece, Giulia Grisi. The eyes were larger and more expressive, and she had more regular features and finer teeth. There was a tragic dignity in the contour and lineaments of her countenance, which formed a strange contrast with her unrefined language and gipsy style of dress; every colour of the rainbow was represented in her garments, which she tied on without the smallest regard to taste, and gave her very much the appearance of a strolling actress equipped at Ragfair.

Grassini’s once fine voice had, when I saw her, degenerated into a sharp, loud, unmelodious soprano, which grated harshly on the ear. She had no cleverness or wit, and the bons mots that are cited as hers are amusing only from the cynic bonhomie which inspired them, as well as the strong Italian accent with which they were spoken. (13)

Giuseppina Grassini died on January 3, 1850 in Milan at the age of 76. An obituary described her as “one of the most celebrated Italian singers, and the most beautiful woman, of her day…. Few of her profession ever boasted of a career so long and so brilliant as hers. In Italy, France, Germany, and England, she achieved for herself the highest reputation, and for many years ruled in undisputed possession on the throne of song.” (14)

You might also enjoy:

What was Napoleon’s favourite music?

Napoleon’s Castrato: Girolamo Crescentini

The Duke of Wellington: Napoleon’s Nemesis

The Duke of Wellington and Women

Songs about Napoleon Bonaparte

What did Napoleon think of women?

François-Joseph Talma, Napoleon’s Favourite Actor

- Arthur Pougin, Une Cantatrice ‘Amie’ de Napolon: Giuseppina Grassini, 1773-1850 (Paris, 1920), p. 9.

- Emmanuel-August-Dieudonné de Las Cases, Mémorial de Sainte Hélène: Journal of the Private Life and Conversations of the Emperor Napoleon at Saint Helena, Vol. III, Part 5 (London, 1823), p. 21.

- Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne, Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte, Vol. II (New York, 1891), p. 395.

- Ibid., p. 395.

- Joseph Fouché, The Memoirs of Joseph Fouché, Duke of Otranto (Boston, 1825), p. 144.

- Richard Edgcumbe, Musical Reminiscences, Containing an Account of the Italian Opera in England, From 1773 Continued to the Present Time, Fourth Edition (London, 1834), pp. 92-94.

- Thomas De Quincey, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (London, 1930), p. 191.

- “Death of Signora Grassini,” The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, Vol. 23 (New York, May 1851), p. 48.

- Madame Ancelot, Les salons de Paris: Foyers éteints (Paris, 1858), p. 34.

- Castalia Countess Granville, ed., Lord Granville Leveson Gower (First Earl Granville) Private Correspondence, 1781 to 1821, Vol. II (London, 1916), p. 507.

- Felice Blangini, Souvenirs de F. Blangini (Paris, 1834), p. 279.

- Adèle d’Osmond, Mémoires de la Comtesse de Boigne, Vol. II, M. Charles Nicoullaud (Paris, 1908), p. 145.

- Rees Howell Gronow, Celebrities of London and Paris: Being a Third Series of Reminiscences and Anecdotes of the Camp, the Court, and the Clubs (London, 1865), pp. 151-154.

- “Death of Madame Grassini,” The Musical World, Vol. 25, No. 4 (London, January 26, 1850), p. 52.

New Year’s Day was a bigger celebration than Christmas in 19th-century France. “Le Jour de l’An, as the French emphatically call it – the day of the year – the day of all others – is a holiday indeed,” reported a London newspaper in 1823. (1) New Year’s Day in Paris was particularly festive, as described in the following accounts.

The Boulevards of Paris on New Year’s Day by Just L’Hernault, 1862

The most remarkable day

“New Year’s Day in Paris is the most remarkable day in the whole year; all the shops are shut; labour suspends his toil; commerce reposes on her oars; and the philosopher postpones his studies…. For several weeks preceding New Year’s Day, various classes of ingenious artists employ all their talents and skill to shine with an uncommon lustre on the auspicious opening of the New Year; these are the confectioners, the embossers of visiting cards, the jewellers, &c.; and their shops on this day display a degree of taste and magnificence difficult to describe, and totally unknown in England. This is the day of universal greetings, of renewing acquaintances, of counting how many links have been broken by time last year in the circles of friendship, and what new ones have replaced them.

“All persons, whatever may be their rank, degree, or profession, form a list of the names of persons whose friendship they wish to preserve or cultivate, to each of these persons a porter is sent, to deliver their card. Those more particularly connected with them by blood or friendship are visited in person; and all who meet embrace on this happy day. Millions of cards are distributed; and nothing is seen in the streets but well-dressed persons going to visit their friends and relations, and renew, in an affectionate manner, all the endearing charms of friendship. On this day, too, parents, friends, and lovers, bestow their presents on the various objects of their affection, & pour out many draughts of the most delightful balm that human nature can partake.” (2)

Visions of sugar plums

“The Parisians pay no honours to the old year; it has performed its office, resigned its place; it is past, gone, dead, defunct; all the harm or the good it could do is done, and there is an end of it. But what a merry welcome is given to its successor! …

“The Jour de l’An is everybody’s holiday, the holiday of all ages, ranks, and conditions. Relations, friends, acquaintances, visit each other, kiss, and exchange sugar plums. For weeks previous to it, all the makers and vendors of fancy articles, from diamond necklaces and tiaras, down to sweetmeat boxes, are busily employed in the preparation of étrennes – New Year’s presents. But the staple commodity of French commerce, at this period, is sugar plums. At all times of the year are the shops of the marchands de bon-bons, in this modern Athens (as the Parisians call Paris), amply stocked, and constant is the demand for their luscious contents; but now the superb magasins in the Rue Vivienne, the splendid boutiques on the Boulevards, the magnificent depots in the Palais Royal, are rich in sweets beyond even that sugary conception, a child’s paradise, and they are literally crowded from morning till night by persons of all ages, men, women, and children.

“Vast and various is the invention of the fabricants of this important necessary of life; and sugar is formed into tasteful imitations of carrots, cupids, ends of candle, roses, sausages, soap, bead-necklaces – all that is nice or nasty in nature and art. Ounce weights are thrown aside, and nothing under dozens of pounds is to be seen on the groaning counters; the wearied vendors forget to number by units, and fly to scores, hundreds, and thousands. But brilliant as are the exhibitions of sugar-work in this gay quarter of the town, they must yield for quantity to the astounding masses of the Rue des Lombards. That is the place resorted to by great purchasers, by such as require not pounds, but hundred weights for distribution. There reside all the mighty compounders, the vendors at first hand; and sugar-plum makers are as numerous in the Parisian Lombard-street, as are the traffickers in douceurs of a more substantial character in its namesake in London.

Engaging a vehicle

“The day has scarcely dawned, and all is life, bustle, and movement. The visiting lists are prepared, the presents arranged, the cards are placed in due order of delivery. Vehicles of all descriptions are already crossing and jostling in every part of the city. Fortunate they are who, unblest with a calèche or a cabriolet of their own, have succeeded in engaging one for the day at six times its ordinary cost.

“On New Year’s Day, the Paris fraternity are allowed the enjoyment of what seems to be their birth-right – rudeness and extortion; or rather the exercise of it is tolerated. There, on yonder deserted stand, are collected eighteen or twenty people who have been waiting the greater part of the morning, the possibility of the arrival of an unhired vehicle. At length – for wonders never case – a cabriolet approaches. It is surrounded, besieged, assaulted, stormed. It is literally put up to auction to be let to the highest bidder. That poor servant of the public, its driver, now finds that the public is his, and his very humble and beseeching servant too. ‘Eh, bien, voyons, combien me donnerez vous?’ – ‘I’ll give you,’ says one, taking out his watch. ‘Au diable, l’imbecile he wants a cabriolet à l’heure on New Year’s Day – to drive him to Pontoise, perhaps.’ (A place celebrated for its calves.) ‘And you there, grand nigaud, with your watch in your hand! À bas les montres, or I’ll listen to none of you. À la course, à la course! And you, ma petite demoiselle, what is it you offer? How! Three francs! Elle est gentile, la petite, avec le trois francs! Allons tout ça m’ennuie. I’ll go take a drive in the Bois de Boulogne for my own pleasure.’ At length he consents to take a little squat négociant at five times the usual fare, exclaiming as he drives off, ‘Ma foi, j’ai trop bon coeur – je me laisse attendrir.’

Visiting, kissing and present-making

Le beau jour des étrennes by Gustave Doré, 1848. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

“That is Mademoiselle –, of the Theatre Français. Her first visit is to Monsieur –, editor of the – journal. Three days ago she received a hint that he had prepared a thundering article against her intended performance of Célimène, which she is to act for the first time on Monday next. The chased silver-gilt soupière at her side is a New Year’s present for Monsieur le Rédacteur. The article will not appear. Her performance will be cited as a model de grâce, d’intelligence, et d’esprit.

“That? – Hush! Turn away, or he will call us out for merely looking at him. Tis Z–, the celebrated duellist. Yesterday he wounded General de B–, the day before he killed M. de C–, and he has an affair in hand for tomorrow. Today he goes about distributing sugar plums, as in duty bound, for c’est un homme très amiable.

“I don’t know either of the two gentlemen who are kissing both sides of each other’s faces, bowing and exchanging little paper packets. The very old man passing close to them, in a single-breasted faded silk coat, the colour of which once was apple blossom, is the younger brother of the Comte de –. He is on his way to pay his annual visit to Mademoiselle –, who was his mistress some years before the breaking out of the Revolution. He stops to purchase a bouquet composed of violets and roses. Violets and roses on New Year’s Day! – his accustomed present. His visit is not one of affection – scarcely of friendship – c’est une affaire d’habitude.

“I am of your opinion that Mademoiselle Entrechat, the opera dancer, is extraordinarily ugly, and of opinion with every one else, that she is a fool. She is handsome enough, however, in the estimation of our countryman, Sir X– Y– (who is economizing in Paris), because she dances, and has just sense enough to dupe him – very little is sufficient. Heaven knows! He is now on his way to her with a splendid cachemire and a few rouleaus. ‘Vraiment, les Anglais sont charmants.’ The poor simpleton believes she means it, and sputters something in unintelligible French in reply: at which Mademoiselle’s brother swears a big oath, that ‘Monsieur l’Anglais à de l’esprit comme quatre.’ Sir X– Y– invites him to dinner, but the Captain ‘makes it a rule to dine with his sister on New Year’s Day.’ O! If some of our poor simple countrymen could but see behind the curtain! But tis their affair, not mine.

“In that cabriolet is an actress who wants to come out at the Comic Opera. What could have put it into her head that Monsieur L–, who has a voice potential in the Theatrical Senate, has just occasion for a breakfast service in Sèvres porcelain!

“Behind is a hackney-coach full of little figurantes, who have clubbed together for the expense of it. They are going to étrenner the ballet-master. One does not like to dance in the rear where nobody can see her; another is anxious to dance seule; a third, the daughter of my washerwoman, is sure she could act Nina, if they would but let her try; a fourth wants the place of ouvreuse de loges for her maman, who sells roasted chestnuts at yonder corner. They offer their sugar plums, but, alas! they lack the gilding. Never despair, young ladies. Emigration is not yet at an end; economy is the order of the day in England, and Paris is the place for economizing in. Next year, perhaps, you too may be provided with eloquent douceurs to soften the hearts of the rulers of your dancing destinies.

Heartless forms?

“So then, it may be asked, is all this visiting, and kissing, and present-making, and sugar-plumizing to be set down, either to the account of sheer interest, or to that of heartless form? Partly to the one, perhaps, partly to the other, and some part of it to a kinder principle than either. But, be it as it may, motives of interest receive a decent covering from the occasion; these heartless forms serve to keep society together; and, without philosophizing the matter, let it be set down that, of all the days in the year, none is so perfect a holiday as New Year’s Day in Paris.” (3)

Happy New Year!

You might also enjoy:

New Year Wishes from the 19th Century

New Year’s Day in 19th-Century New York

Napoleon’s First New Year’s Day on St. Helena

The New Year’s Day Reflections of John Quincy Adams

Celebrating a 19th-Century Christmas

Christmas Gift Ideas from the 19th Century

Sweetbreads, Sweetmeats and Bonaparte’s Ribs

The Palais-Royal: Social Centre of 19th-Century Paris

Napoleon’s Funeral in Paris in 1840

- “New Year’s Day in Paris,” The Times (London), January 1, 1823, p. 3.

- “New Year’s Day,” Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette (Devizes, England), December 26, 1822, p. 2.

- “New Year’s Day in Paris,” The Times (London), January 1, 1823, p. 3.

European immigrants brought many Christmas traditions to America between the 17th and 19th centuries. Pennsylvania, with its mix of Swedish, Dutch, Quaker, German, French, Welsh, Scots-Irish and other settlers, had a rich assortment of Christmas customs to draw upon. Joseph Bonaparte and the other Napoleonic exiles who settled in the Philadelphia area after 1815 probably encountered some of the Christmas Eve traditions described in the following article, which appeared in a Philadelphia newspaper in 1827.

European immigrants brought many Christmas traditions to America between the 17th and 19th centuries. Pennsylvania, with its mix of Swedish, Dutch, Quaker, German, French, Welsh, Scots-Irish and other settlers, had a rich assortment of Christmas customs to draw upon. Joseph Bonaparte and the other Napoleonic exiles who settled in the Philadelphia area after 1815 probably encountered some of the Christmas Eve traditions described in the following article, which appeared in a Philadelphia newspaper in 1827.

Christmas Eve in the countryside

“We like a holiday, and so does every care-worn, labour-stricken animal in the community, and the preparation, preliminaries, and anticipations of a pleasure are frequently quite as agreeable as the reality. Of all the religious festivities, none are so religiously observed and kept in the interior of our state, especially in the German districts, as Christmas. It is the Thanksgiving day of New England. Every one that can so time it, ‘kills’ before the holidays, and a general sweep is made among pigs and poultry, cakes and mince pies. Christmas Eve too, is an important era, especially to the young urchins, and has its appropriate ceremonies, of which hanging up the stockings is not the least momentous. ‘Bellschniggle,’ ‘Christkindle’ or ‘St. Nicholas,’ punctually perform their rounds, and bestow rewards and punishments as occasion may require.

Bellschniggle